Key Points

-

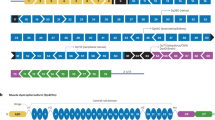

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common X-linked neuromuscular disease. It is caused by mutations in the DMD gene that lead to abnormalities of dystrophin protein expression in muscle. DMD is fatal and currently incurable.

-

Well-characterized animal models for DMD exist, as do well-characterized and sensitive anatomical, biochemical and physiological methods for evaluating a therapeutic intervention in animal models of DMD.

-

Gene therapy approaches (using both vector and vectorless strategies), as well as cell-based therapies (using myoblasts and stem cells) have met with some success in pre-clinical studies. They currently face a number of technical challenges.

-

Pharmacological strategies can circumvent many of the hurdles that currently hamper gene- and cell-based therapies.

-

This review covers a number of promising pharmacological strategies such as steroids, maintaining calcium homeostasis, decreasing inflammation, increasing muscle strength, suppressing stop codons, upregulation of utrophin, and increasing muscle mass via modulation of growth/developmental factors.

-

Strategies associated with utrophin upregulation and increasing muscle mass via modulation of growth/developmental factors are covered in some detail.

Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a fatal, genetic disorder whose relentless progression underscores the urgency for developing a cure. Although Duchenne initiated clinical trials roughly 150 years ago, therapies for DMD remain supportive rather than curative. A paradigm shift towards developing rational therapeutic strategies occurred with identification of the DMD gene. Gene- and cell-based therapies designed to replace the missing gene and/or dystrophin protein have achieved varying degrees of success. However, pharmacological strategies not designed to replace dystrophin per se appear promising, and can circumvent many hurdles hampering gene- and cell-based therapy. Here, we will review present pharmacological strategies, in particular those dealing with functional substitution of dystrophin by utrophin and enhancing muscle progenitor commitment by myostatin blockade, with a view toward facilitating drug discovery for DMD.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Duchenne, G. B. A. Recherches sur la paralysie musculaire pseudohypertrophique ou paralysie myo-sclerosique. Arch. Gen. Med. 11, 5–528 (1868).

Monaco, A. P. et al. Isolation of candidate cDNAs for portions of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene. Nature 323, 646–650 (1986).

Hoffman, E. P., Brown, R. H. & Kunkel, L. M. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell 51, 919–928 (1987).

Koenig, M., Monaco, A. P. & Kunkel, L. M. The complete sequence of dystrophin predicts a rod-shaped cytoskeletal protein. Cell 53, 219–226 (1988). References 1–4 are classic papers describing DMD and elucidating its cause.

Love, D. R. et al. An autosomal transcript in skeletal muscle with homology to dystrophin. Nature 339, 55–58 (1989).

Khurana, T. S., Hoffman, E. P. & Kunkel, L. M. Identification of a chromosome 6-encoded dystrophin-related protein. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 16717–16720 (1990).

Tinsley, J. M. et al. Primary structure of dystrophin-related protein. Nature 360, 591–593 (1992). References 5–7 describe the identification of the dystrophin-related protein utrophin.

Roberts, R. G. et al. Characterization of DRP2, a novel human dystrophin homologue. Nature Genet. 13, 223–226 (1996).

Khurana, T. S. et al. (CA) repeat polymorphism in the chromosome 18 encoded dystrophin-like protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 3, 841 (1994).

Sadoulet, P. H., Khurana, T. S., Cohen, J. B. & Kunkel, L. M. Cloning and characterization of the human homologue of a dystrophin related phosphoprotein found at the Torpedo electric organ post-synaptic membrane. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5, 489–496 (1996).

Blake, D. J., Nawrotzki, R., Peters, M. F., Froehner, S. C. & Davies, K. E. Isoform diversity of dystrobrevin, the murine 87-kDa postsynaptic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 7802–7810 (1996).

Campbell, K. P. Three muscular dystrophies: loss of cytoskeletal extracellular matrix linkage. Cell 80, 675–679 (1995).

Ervasti, J. M. & Campbell, K. P. Membrane organization of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex. Cell 66, 1121–1131 (1991).

Matsumura, K., Ervasti, J. M., Ohlendieck, K., Kahl, S. D. & Campbell, K. P. Association of dystrophin-related protein with dystrophin-associated proteins in mdx mouse muscle. Nature 360, 588–591 (1992).

Emery, A. E. H. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (Oxford University Press, 1993).

Engel, A. G. & Franzini-Armstrong, C. Myology (McGraw–Hill, New York, 1994).

Karpati, G. & Carpenter, S. Small-calibre skeletal muscle fibers do not suffer deleterious consequences of dystrophic gene expression. Am. J. Med. Genet. 25, 653–658 (1986).

Kaminski, H. J., al-Hakim, M., Leigh, R. J., Katirji, M. B. & Ruff, R. L. Extraocular muscles are spared in advanced Duchenne dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 32, 586–588 (1992).

Khurana, T. S. et al. Absence of extraocular muscle pathology in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy: role for calcium homeostasis in extraocular muscle sparing. J. Exp. Med. 182, 467–475 (1995).

Allamand, V. & Campbell, K. P. Animal models for muscular dystrophy: valuable tools for the development of therapies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2459–2467 (2000).

Bulfield, G., Siller, W. G., Wight, P. A. & Moore, K. J. X chromosome-linked muscular dystrophy (mdx) in the mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 81, 1189–1192 (1984).

Cooper, B. J. et al. The homologue of the Duchenne locus is defective in X-linked muscular dystrophy of dogs. Nature 334, 154–156 (1988).

Carpenter, J. L. et al. Feline muscular dystrophy with dystrophin deficiency. Am. J. Pathol. 135, 909–919 (1989). References 21–23 identified genuine animal models for DMD that are invaluable for preclinical therapeutic studies.

Schatzberg, S. J. et al. Molecular analysis of a spontaneous dystrophin 'knockout' dog. Neuromuscul. Disord. 9, 289–295 (1999).

Chapman, V. M., Miller, D. R., Armstrong, D. & Caskey, C. T. Recovery of induced mutations for X chromosome-linked muscular dystrophy in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 1292–1296 (1989).

Stedman, H. H. et al. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature 352, 536–539 (1991).

Moens, P., Baatsen, P. H. & Marechal, G. Increased susceptibility of EDL muscles from mdx mice to damage induced by contractions with stretch. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 14, 446–451 (1993).

Petrof, B. J., Shrager, J. B., Stedman, H. H., Kelly, A. M. & Sweeney, H. L. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 3710–3714 (1993). References 26–28 characterize functional deficits in mdx muscle and provide ex vivo experimental paradigms for evaluation of therapeutic interventions.

Gillis, J. M. & Deconinck, N. The physiological evaluation of gene therapies of dystrophin-deficient muscles. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 453, 411–416; discussion 417 (1998).

Krag, T. O., Gyrd-Hansen, M. & Khurana, T. S. Harnessing the potential of dystrophin-related proteins for ameliorating Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. Acta Physiol. Scand. 171, 349–358 (2001).

Gillis, J. M. Multivariate evaluation of the functional recovery obtained by the overexpression of utrophin in skeletal muscles of the mdx mouse. Neuromuscul. Disord. 12 Suppl. 1, 90–94 (2002).

Deconinck, A. E. et al. Utrophin–dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell 90, 717–727 (1997).

Grady, R. M. et al. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell 90, 729–738 (1997).

Morrison, J., Lu, Q. L., Pastoret, C., Partridge, T. & Bou-Gharios, G. T-cell-dependent fibrosis in the mdx dystrophic mouse. Lab. Invest. 80, 881–891 (2000).

Keep, N. H., Norwood, F. L., Moores, C. A., Winder, S. J. & Kendrick-Jones, J. The 2.0 A structure of the second calponin homology domain from the actin-binding region of the dystrophin homologue utrophin. J. Mol. Biol. 285, 1257–1264 (1999).

Winder, S. J. et al. Utrophin actin binding domain: analysis of actin binding and cellular targeting. J. Cell Sci. 108, 63–71 (1995).

Winder, S. J., Gibson, T. J. & Kendrick, J. J. Dystrophin and utrophin: the missing links. FEBS Lett. 369, 27–33 (1995).

Blake, D. J., Weir, A., Newey, S. E. & Davies, K. E. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol. Rev. 82, 291–329 (2002).

Adams, M. E. et al. Absence of α-syntrophin leads to structurally aberrant neuromuscular synapses deficient in utrophin. J. Cell. Biol. 150, 1385–1398 (2000).

Love, D. R. et al. Tissue distribution of the dystrophin-related gene product and expression in the mdx and dy mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 3243–3247 (1991).

Khurana, T. S. et al. Immunolocalization and developmental expression of dystrophin related protein in skeletal muscle. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1, 185–194 (1991).

Nguyen, T. M. et al. Localization of the DMDL gene-encoded dystrophin-related protein using a panel of nineteen monoclonal antibodies: presence at neuromuscular junctions, in the sarcolemma of dystrophic skeletal muscle, in vascular and other smooth muscles, and in proliferating brain cell lines. J. Cell Biol. 115, 1695–1700 (1991).

Ohlendieck, K. et al. Dystrophin-related protein is localized to neuromuscular junctions of adult skeletal muscle. Neuron 7, 499–508 (1991).

Byers, T. J., Kunkel, L. M. & Watkins, S. C. The sub-cellular distribution of dystrophin in mouse skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle. J. Cell Biol. 115, 411–421 (1991).

Bewick, G. S., Nicholson, L. V., Young, C., O'Donnell, E. & Slater, C. R. Different distributions of dystrophin and related proteins at nerve-muscle junctions. Neuroreport 3, 857–860 (1992).

Clerk, A., Morris, G. E., Dubowitz, V., Davies, K. E. & Sewry, C. A. Dystrophin-related protein, utrophin, in normal and dystrophic human fetal skeletal muscle. Histochem. J. 25, 554–561 (1993).

Pons, F., Nicholson, L. V., Robert, A., Voit, T. & Leger, J. J. Dystrophin and dystrophin-related protein (utrophin) distribution in normal and dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscles. Neuromuscul. Disord. 3, 507–514 (1993).

Radojevic, V., Lin, S. & Burgunder, J. M. Differential expression of dystrophin, utrophin, and dystrophin-associated proteins in human muscle culture. Cell Tissue Res. 300, 447–457 (2000).

Deconinck, A. E. et al. Postsynaptic abnormalities at the neuromuscular junctions of utrophin-deficient mice. J. Cell. Biol. 136, 883–894 (1997).

Grady, R. M., Merlie, J. P. & Sanes, J. R. Subtle neuromuscular defects in utrophin-deficient mice. J. Cell. Biol. 136, 871–882 (1997).

Rafael, J. A., Tinsley, J. M., Potter, A. C., Deconinck, A. E. & Davies, K. E. Skeletal muscle-specific expression of a utrophin transgene rescues utrophin-dystrophin deficient mice. Nature Genet. 19, 79–82 (1998).

Tinsley, J. et al. Expression of full-length utrophin prevents muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Nature Med. 4, 1441–1444 (1998).

Tinsley, J. M. et al. Amelioration of the dystrophic phenotype of mdx mice using a truncated utrophin transgene. Nature 384, 349–353 (1996). Reference 53 provides the proof of principle that utrophin can functionally substitute for dystrophin in vivo.

Wakefield, P. M. et al. Prevention of the dystrophic phenotype in dystrophin/utrophin-deficient muscle following adenovirus-mediated transfer of a utrophin minigene. Gene Ther. 7, 201–204 (2000).

Pearce, M. et al. The utrophin and dystrophin genes share similarities in genomic structure. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2, 1765–1772 (1993).

Jimenez-Mallebrera, C., Davies, K., Putt, W. & Edwards, Y. H. A study of short utrophin isoforms in mice deficient for full-length utrophin. Mamm. Genome 14, 47–60 (2003).

Dennis, C. L., Tinsley, J. M., Deconinck, A. E. & Davies, K. E. Molecular and functional analysis of the utrophin promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 1646–1652 (1996).

Burton, E. A., Tinsley, J. M., Holzfeind, P. J., Rodrigues, N. R. & Davies, K. E. A second promoter provides an alternative target for therapeutic up-regulation of utrophin in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14025–14030 (1999).

Galvagni, F. & Oliviero, S. Utrophin transcription is activated by an intronic enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 3168–3172 (2000).

Weir, A. P., Burton, E. A., Harrod, G. & Davies, K. E. A- and B-utrophin have different expression patterns and are differentially up-regulated in mdx muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45285–45290 (2002).

Schaeffer, L., de Kerchove d'Exaerde, A. & Changeux, J. P. Targeting transcription to the neuromuscular synapse. Neuron 31, 15–22 (2001).

Buonanno, A. & Fischbach, G. D. Neuregulin and ErbB receptor signaling pathways in the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11, 287–296 (2001).

Gramolini, A. O. et al. Induction of utrophin gene expression by heregulin in skeletal muscle cells: role of the N-box motif and GA binding protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3223–3227 (1999).

Khurana, T. S. et al. Activation of utrophin promoter by heregulin via the ets-related transcription factor complex GA-binding protein α/β. Mol. Biol. Cell. 10, 2075–2086 (1999).

Galvagni, F., Capo, S. & Oliviero, S. Sp1 and Sp3 physically interact and co-operate with GABP for the activation of the utrophin promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 306, 985–996 (2001).

Perkins, K. J., Burton, E. A. & Davies, K. E. The role of basal and myogenic factors in the transcriptional activation of utrophin promoter A: implications for therapeutic up-regulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4843–4850 (2001).

Gyrd-Hansen, M., Krag, T. O., Rosmarin, A. G. & Khurana, T. S. Sp1 and the ets-related transcription factor complex GABP α/β functionally cooperate to activate the utrophin promoter. J. Neurol. Sci. 197, 27–35 (2002).

Perkins, K. J. & Davies, K. E. Ets, Ap-1 and GATA factor families regulate the utrophin B promoter; potential regulatory mechanisms for endothelial-specific expression. FEBS Lett. 538, 168–172 (2003).

Briguet, A., Bleckmann, D., Bettan, M., Mermod, N. & Meier, T. Transcriptional activation of the utrophin promoter B by a constitutively active Ets-transcription factor. Neuromuscul. Disord. 13, 143–150 (2003).

Chaubourt, E. et al. Nitric oxide and l-arginine cause an accumulation of utrophin at the sarcolemma: a possible compensation for dystrophin loss in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurobiol. Dis. 6, 499–507 (1999).

Chaubourt, E. et al. Muscular nitric oxide synthase (muNOS) and utrophin. J. Physiol. Paris 96, 43–52 (2002).

Burkin, D. J., Wallace, G. Q., Nicol, K. J., Kaufman, D. J. & Kaufman, S. J. Enhanced expression of the α7β1 integrin reduces muscular dystrophy and restores viability in dystrophic mice. J. Cell. Biol. 152, 1207–1218 (2001).

Nguyen, H. H., Jayasinha, V., Xia, B., Hoyte, K. & Martin, P. T. Overexpression of the cytotoxic T cell GalNAc transferase in skeletal muscle inhibits muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5616–5621 (2002).

Gramolini, A. O., Belanger, G., Thompson, J. M., Chakkalakal, J. V. & Jasmin, B. J. Increased expression of utrophin in a slow vs. a fast muscle involves posttranscriptional events. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 281, C1300–C1309 (2001).

Courdier-Fruh, I., Barman, L., Briguet, A. & Meier, T. Glucocorticoid-mediated regulation of utrophin levels in human muscle fibers. Neuromuscul. Disord. 12, S95–S104 (2002).

Fisher, R. et al. Non-toxic ubiquitous over-expression of utrophin in the mdx mouse. Neuromuscul. Disord. 11, 713–721 (2001).

Squire, S. et al. Prevention of pathology in mdx mice by expression of utrophin: analysis using an inducible transgenic expression system. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 3333–3344 (2002).

Cerletti, M. et al. The dystrophic phenotype of canine X-linked muscular dystrophy is mitigated by adenovirus-mediated utrophin gene transfer. Gene Ther. (In the press).

Thioudellet, C., Blot, S., Squiban, P., Fardeau, M. & Braun, S. Current protocol of a research phase I clinical trial of full-length dystrophin plasmid DNA in Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophies. Part I: rationale. Neuromuscul. Disord. 12, S49–S51 (2002).

Romero, N. B. et al. Current protocol of a research phase I clinical trial of full-length dystrophin plasmid DNA in Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophies. Part II: clinical protocol. Neuromuscul. Disord. 12, S45–S48 (2002).

Barthelmai, W. On the effect of corticoid administration on creatine phosphokinase in progressive muscular dystrophy. Verh. Dtsch Ges. Inn. Med. 71, 624–626 (1965).

Drachman, D. B., Toyka, K. V. & Myer, E. Prednisone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Lancet 2, 1409–1412 (1974). References 81–82 describe the use of steroids in pharmacological therapy of DMD.

Mendell, J. R. et al. Randomized, double-blind six-month trial of prednisone in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 320, 1592–1597 (1989).

Sansome, A., Royston, P. & Dubowitz, V. Steroids in Duchenne muscular dystrophy; pilot study of a new low-dosage schedule. Neuromuscul. Disord. 3, 567–569 (1993).

Bonifati, M. D. et al. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial of deflazacort versus prednisone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 23, 1344–1347 (2000).

Manzur, A. Y. in The Muscular Dystrophies (ed. Emery, A. E. H.) 223–246 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Bodensteiner, J. B. & Engel, A. G. Intracellular calcium accumulation in Duchenne dystrophy and other myopathies: a study of 567,000 muscle fibers in 114 biopsies. Neurology 28, 439–446 (1978).

Fischer, M. D. et al. Expression profiling reveals metabolic and structural components of extraocular muscles. Physiol. Genomics 9, 71–84 (2002).

Fong, P. Y., Turner, P. R., Denetclaw, W. F. & Steinhardt, R. A. Increased activity of calcium leak channels in myotubes of Duchenne human and mdx mouse origin. Science 250, 673–676 (1990).

Turner, P. R., Schultz, R., Ganguly, B. & Steinhardt, R. A. Proteolysis results in altered leak channel kinetics and elevated free calcium in mdx muscle. J. Membr. Biol. 133, 243–251 (1993).

De Backer, F., Vandebrouck, C., Gailly, P. & Gillis, J. M. Long-term study of Ca2+ homeostasis and of survival in collagenase-isolated muscle fibres from normal and mdx mice. J. Physiol. 542, 855–865 (2002).

Bertorini, T. E. et al. Effect of dantrolene in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 14, 503–507 (1991).

Badalamente, M. A. & Stracher, A. Delay of muscle degeneration and necrosis in mdx mice by calpain inhibition. Muscle Nerve 23, 106–111 (2000).

Spencer, M. J. & Mellgren, R. L. Overexpression of a calpastatin transgene in mdx muscle reduces dystrophic pathology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 2645–2655 (2002).

Wrogemann, K. & Pena, S. D. Mitochondrial calcium overload: A general mechanism for cell-necrosis in muscle diseases. Lancet 1, 672–674 (1976).

Arahata, K. & Engel, A. G. Monoclonal antibody analysis of mononuclear cells in myopathies. I: Quantitation of subsets according to diagnosis and sites of accumulation and demonstration and counts of muscle fibers invaded by T cells. Ann. Neurol. 16, 193–208 (1984).

Engel, A. G. & Arahata, K. Monoclonal antibody analysis of mononuclear cells in myopathies. II: Phenotypes of autoinvasive cells in polymyositis and inclusion body myositis. Ann. Neurol. 16, 209–215 (1984).

Arahata, K. & Engel, A. G. Monoclonal antibody analysis of mononuclear cells in myopathies. III: Immunoelectron microscopy aspects of cell-mediated muscle fiber injury. Ann. Neurol. 19, 112–125 (1986). References 96–98 suggest a role for cellular immunity in DMD.

Gorospe, J., Tharp, M. D., Hinckley, J., Kornegay, J. N. & Hoffman, E. P. A role for mast cells in the progression of Duchenne muscular dystrophy? Correlations in dystrophin-deficient humans, dogs, and mice. J. Neurol. Sci. 122, 44–56 (1994).

Chen, Y. -W., Zhao, P., Borup, R. & Hoffman, E. P. Expression profiling in the muscular dystrophies: Identification of novel aspects of molecular pathophysiology. J. Cell. Biol. 151, 1321–1326 (2000).

Haslett, J. N. et al. Gene expression comparison of biopsies from Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and normal skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15000–15005 (2002).

D'Amore, P. A. et al. Elevated basic fibroblast growth factor in the serum of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 35, 362–365 (1994).

Spencer, M. J., Montecino-Rodriguez, E., Dorshkind, K. & Tidball, J. G. Helper (CD4+) and cytotoxic (CD8+) T cells promote the pathology of dystrophin-deficient muscle. Clin. Immunol. 98, 235–243 (2001).

Granchelli, J. A., Pollina, C. & Hudecki, M. S. Duchenne-like myopathy in double-mutant mdx mice expressing exaggerated mast cell activity. J. Neurol. Sci. 131, 1–7 (1995).

Granchelli, J. A., Avosso, D. L., Hudecki, M. S. & Pollina, C. Cromolyn increases strength in exercised mdx mice. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 91, 287–296 (1996).

Zeman, R. J., Zhang, Y. & Etlinger, J. D. Clenbuterol, a β2-agonist, retards wasting and loss of contractility in irradiated dystrophic mdx muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 267, C865–C868 (1994).

Pulido, S. M. et al. Creatine supplementation improves intracellular Ca2+ handling and survival in mdx skeletal muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 439, 357–362 (1998).

Walter, M. C. et al. Creatine monohydrate in muscular dystrophies: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Neurology 54, 1848–1850 (2000).

Barton-Davis, E. R., Cordier, L., Shoturma, D. I., Leland, S. E. & Sweeney, H. L. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore dystrophin function to skeletal muscles of mdx mice. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 375–381 (1999).

Wagner, K. R. et al. Gentamicin treatment of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy due to nonsense mutations. Ann. Neurol. 49, 706–711 (2001).

Barton, E. R., Morris, L., Musaro, A., Rosenthal, N. & Sweeney, H. L. Muscle-specific expression of insulin-like growth factor I counters muscle decline in mdx mice. J. Cell. Biol. 157, 137–148 (2002).

Gregorevic, P., Plant, D. R., Leeding, K. S., Bach, L. A. & Lynch, G. S. Improved contractile function of the mdx dystrophic mouse diaphragm muscle after insulin-like growth factor-I administration. Am. J. Pathol. 161, 2263–2272 (2002). References 111–112 demonstrate increasing muscle mass as a therapeutic strategy in DMD.

De Luca, A. et al. Enhanced dystrophic progression in mdx mice by exercise and beneficial effects of taurine and insulin-like growth factor-1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 304, 453–463 (2003).

Charlier, C. et al. The mh gene causing double-muscling in cattle maps to bovine chromosome 2. Mamm. Genome 6, 788–792 (1995).

Grobet, L. A deletion in the bovine myostatin gene causes the double-muscled phenotype in cattle. Nature Genet. 1, 71–74 (1997).

McPherron, A. C., Lawler, A. M. & Lee, S. J. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-β superfamily member. Nature 387, 83–90 (1997). References 115 and 116 identify myostatin as a potent regulator of muscle progenitor cells.

Nishi, M. et al. A missense mutant myostatin causes hyperplasia without hypertrophy in the mouse muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293, 247–251 (2002).

Zhu, X., Hadhazy, M., Wehling, M., Tidball, J. G. & McNally, E. M. Dominant negative myostatin produces hypertrophy without hyperplasia in muscle. FEBS Lett. 474, 71–75 (2000).

Thies, R. S. et al. GDF-8 propeptide binds to GDF-8 and antagonizes biological activity by inhibiting GDF-8 receptor binding. Growth Factors 18, 251–259 (2001).

Lee, S. J. Regulation of myostatin activity and muscle growth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9306–9311 (2001).

Thomas, M. et al. Myostatin, a negative regulator of muscle growth, functions by inhibiting myoblast proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40235–40243 (2000).

Spiller, M. P. et al. The myostatin gene is a downstream target gene of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor MyoD. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 7066–7082 (2002).

Langley, B. et al. Myostatin inhibits myoblast differentiation by down-regulating MyoD expression. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49831–49840 (2002).

Bogdanovich, S. et al. Functional improvement of dystrophic muscle by myostatin blockade. Nature 420, 418–421 (2002). Reference 124 demonstrates myostatin blockade as a pharmacological strategy in DMD.

Wagner, K. R., McPherron, A. C., Winik, N. & Lee, S. J. Loss of myostatin attenuates severity of muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Ann. Neurol. 52, 832–836 (2002).

Escolar, D. M., Henricson, E. K., Pasquali, L., Gorni, K. & Hoffman, E. P. Collaborative translational research leading to multicenter clinical trials in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: the Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group (CINRG). Neuromuscul. Disord. 12, S147–S154 (2002).

Granchelli, J. A., Pollina, C. & Hudecki, M. S. Pre-clinical screening of drugs using the mdx mouse. Neuromuscul. Disord. 10, 235–239 (2000).

Ragot, T. et al. Efficient adenovirus-mediated transfer of a human minidystrophin gene to skeletal muscle of mdx mice. Nature 361, 647–650 (1993).

Mann, C. J. et al. Antisense-induced exon skipping and synthesis of dystrophin in the mdx mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 42–47 (2001).

van Deutekom, J. C. et al. Antisense-induced exon skipping restores dystrophin expression in DMD patient derived muscle cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 1547–1554 (2001).

Bartlett, R. J. et al. In vivo targeted repair of a point mutation in the canine dystrophin gene by a chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotide. Nature Biotechnol. 18, 615–622 (2000).

Rando, T. A., Disatnik, M. H. & Zhou, L. Z. Rescue of dystrophin expression in mdx mouse muscle by RNA/DNA oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5363–5368 (2000).

Partridge, T. A., Morgan, J. E., Coulton, G. R., Hoffman, E. P. & Kunkel, L. M. Conversion of mdx myofibres from dystrophin-negative to -positive by injection of normal myoblasts. Nature 337, 176–179 (1989).

Bittner, R. E. et al. Recruitment of bone-marrow-derived cells by skeletal and cardiac muscle in adult dystrophic mdx mice. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 199, 391–396 (1999).

Gussoni, E. et al. Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse restored by stem cell transplantation. Nature 401, 390–394 (1999). References 128–135 describe a variety of gene and cell-based therapies for DMD.

Sgouras, D. N. et al. ERF: an ets domain protein with strong transcriptional repressor activity, can suppress ets–associated tumorigenesis and is regulated by phosphorylation during cell cycle and mitogenic stimulation. EMBO J. 14, 4781–4793 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this article to the memory of our colleague K. Arahata, whose tireless efforts and scholarship serve as an inspiration in the quest for a cure. We are indebted to the patients, families and organizations who have donated the samples and provided the funding that makes our research possible. Supported by grants from The Medical Research Council (UK), The Muscular Dystrophy Group (UK), Association Contre les Myopathies (France), Duchenne Parents Project (The Netherlands), The Muscular Dystrophy Association (USA) and the National Institutes of Health (USA). We are grateful to S. Bogdanovich, T. Krag and K. Perkins for contributing illustrations and tables. We thank them, as well as numerous other colleagues, for insightful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Related links

Related links

DATABASES

LocusLink

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

FURTHER INFORMATION

Encyclopedia of Life Sciences

Glossary

- DUCHENNE MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY

-

(DMD) A common, genetic neuromuscular disease associated with progressive deterioration of muscle function. In about a third of cases DMD is also associated with impairment of cognitive ability.

- DYSTROPHIN-RELATED PROTEINS

-

A family of proteins that are structurally and functionally related to dystrophin, consisting of utrophin or DRP, DRP2 and dystrobrevin. Utrophin seems capable of functionally substituting for the missing dystrophin and improving muscle pathology when experimentally overexpressed.

- SARCOLEMMA

-

A thin membrane enclosing a striated muscle fibre.

- REGENERATION

-

Muscle has limited ability to regenerate and repair itself when damaged. Cells contained within mature muscle known as satellite cells (sometimes referred to as committed stem cells), proliferate in response to damage and attempt to repair it.

- NECROSIS

-

The death of a cell due to external damage or the action of toxic substances. Distinct from programmed cell death (apoptosis), which is a normal part of the developmental process.

- ECCENTRIC CONTRACTION

-

Skeletal muscle usually contracts when stimulated. Lengthening of muscle during an active contraction is known as an eccentric contraction (ECC). Dystrophic muscle is particularly susceptible to damage during ECC.

- PROMOTER

-

A region of a gene that controls expression of that gene. Its activity is controlled by transcription factors that in turn are activated or repressed by a number of extra- and intracellular mechanisms.

- MYOGENIC

-

Originating in or produced by muscle cells.

- MYOBLAST

-

An undifferentiated cell in the mesoderm of the vertebrate embryo that is a precursor of a muscle cell.

- CALCIUM HOMEOSTASIS

-

The ability of a cell to maintain the requisite intracellular calcium concentration. The body and individual cells have homeostatic mechanisms that can compensate or buffer the lowering or excess levels of intracellular calcium to some degree.

- SARCOPLASMIC RETICULUM

-

A meshwork of internal membranes in muscle cells or fibres.

- MYOTUBE

-

A muscle fibre precursor formed by the fusion of myoblasts.

- LUCIFERASE

-

The enzyme that catalyses the oxidation of luciferin, a reaction that produces bioluminescence.

- INCREASING MUSCLE MASS

-

Muscle mass can increase in response to a variety of physiological and pathological stimuli. Growth/developmental factors regulate muscle mass by complex mechanisms including regulation of the proliferation and differentiation of muscle precursor cells.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khurana, T., Davies, K. Pharmacological strategies for muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2, 379–390 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1085

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1085

This article is cited by

-

Endogenous bioluminescent reporters reveal a sustained increase in utrophin gene expression upon EZH2 and ERK1/2 inhibition

Communications Biology (2023)

-

High-throughput identification of post-transcriptional utrophin up-regulators for Duchenne muscle dystrophy (DMD) therapy

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Deiodinases and stem cells: an intimate relationship

Journal of Endocrinological Investigation (2018)

-

Pharmacological inhibition of REV-ERB stimulates differentiation, inhibits turnover and reduces fibrosis in dystrophic muscle

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

UtroUp is a novel six zinc finger artificial transcription factor that recognises 18 base pairs of the utrophin promoter and efficiently drives utrophin upregulation

BMC Molecular Biology (2013)