Key Points

-

Demonstrates that the use of WPAs in vocational training leads to improved patient care.

-

Highlights the value of feedback in WPAs.

-

Highlights that WPAs aid reflection among foundation dentists.

-

Suggests that WPAs are useful to direct learning.

Abstract

Objective The aims of this survey were to evaluate the effectiveness of workplace based assessments (WPAs) in dental foundation training (formerly vocational training [VT]).

Methods Two online questionnaire surveys were sent to 53 foundation dental practitioners (FDPs) and their 51 trainers in the Mersey Deanery at month four and month nine of the one year of dental foundation training. The questionnaires investigated the effectiveness of and trainers' and trainees' satisfaction with the WPAs used in foundation training, namely dental evaluation of performance (D-EPs), case-based discussions (DcBD) and patients' assessment questionnaires (PAQs). The questionnaires also investigated the perceived impact of reflection and feedback associated with WPAs on clinical practise and improving patient care.

Results A total of 41 (7.4%) FDPs and 44 (86.3%) trainers responded. Of the 41 FDPs, the majority found that feedback from WPAs had a positive effect on their training, giving them insight into their development needs. Overall 84.1% of the FDPs felt the WPAs helped them improve patient care and 82.5% of trainers agreed with that outcome.

Conclusions The findings from this study demonstrate the value of WPAs in dental foundation training by the use of feedback and reflection in directing the learning of foundation dental practitioners and that this can lead to improved clinical practise and patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vocational training (VT) in dentistry in the UK has been mandatory since 1992 for all UK dental graduates who wish to work in the NHS dental services. In England the Performers List Regulations 20051 made it essential for all dentists to have either completed VT, be exempt from VT or to demonstrate competency through assessments equivalent to VT. Vocational training consists of one year spent in a training practice during which trainees undertake an educational day release programme designed to develop clinical skills, knowledge and attitudes required to practice safely.

A number of methods have been used to assess satisfactory completion of VT, most of which have focused on the progress of the vocational dental practitioner (VDP) by way of a personal development portfolio.2 Other methods of assessment have included the completion of Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK) key skills and a clinical audit. These have been found to be valuable in assessing some areas of competence, but both trainers and trainees felt that the direct observation of performance was the best way to assess clinical performance and development.3

Recently there has been a move to more structured training for graduates through foundation training. A UK-wide curriculum for dental foundation training was developed as a result of the Department of Health's work with the UK Dental General Professional Training Liaison Group.4 This recommended the use of workplace based assessments (WPAs) as part of the overall assessment strategy for demonstration of satisfactory completion of training.

To encourage an approach nationally and ensure all aspects of the curriculum were assessed, the Committee of Postgraduate Dental Deans and Directors (COPDEND) commissioned the design of a portfolio with specific dental WPAs. It was at this stage that vocational training became known as foundation training.

The new portfolio assessments consist of dental evaluation of performance (D-EPs), which is a combination of a direct observation of procedure (DOP) with a mini clinical evaluation exercise (miniCEX), a case based discussion tool (DcBD) and a patient assessment questionnaire (PAQ).5 The portfolio was designed to highlight any areas of weaknesses that trainees may have and provide the opportunity for feedback and thereby direct learning.

The importance of feedback in a training environment is essential to promoting positive and desirable development.6 It has been shown that assessment tools which implement feedback are valuable tools for formative learning and assessment of clinical practise, but their effect on students' self-directed learning is dependent on feedback and support from tutors.7,8,9 In a systematic review on assessment, feedback and physicians' clinical performance it was concluded that feedback can change clinical performance when it is systematically delivered from credible sources.10 All WPAs result in direct and immediate feedback which is considered essential in experiential learning.11 There have been some specific evaluations of WPAs in medical training12,13 but in dental training there is little evidence of the evaluation of WPAs other than the work associated with longitudinal evaluation of performance in Scotland.14

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and value of WPAs in foundation dental training by both trainers and trainees in Mersey Deanery.

Methods

The sample consisted of all current trainers (51) and foundation dental practitioners (53) in the Mersey Deanery in 2009. Ethical approval was granted by the University Research Ethics Committee.

An anonymous questionnaire was designed to evaluate the WPAs in foundation training. The questionnaire was informed by focus groups of trainers and trainees and included both open and closed questions and included the use of rating scales. The questionnaire was piloted by all members of the research team and selected trainers. Comments made through piloting were incorporated into the questionnaires.

The questionnaire consisted of four sections, the first investigating demographic information, and then subsequent sections regarding D-EPs, and PAQs focused on the use of feedback and the extent to which trainees and trainers felt that WPAs had improved patient care and clinical practise.

The survey was distributed by email individually in month four of the training year to all current trainers and FDP trainees. The email contained a link to the online questionnaire via Survey Monkey ™ and an information sheet which described the study in detail. Each email contained a randomly allocated study number that respondents inserted at the beginning of the survey. This allowed reminder emails to be sent only to the non-responding trainers and trainees two weeks and four weeks after initial distribution. Only the non-clinical research assistant had access to this information15 and the randomly allocated numbers were at no time linked with the responses received.

A secondary questionnaire was sent to the foundation one trainees at month nine of the training year to report on the use of PAQs. At this time a retrospective reflection from trainees at the end of their year on how useful they found WPAs was also investigated.

Analysis

All quantitative data was input into an Excel database. From this database frequencies were used to examine the distribution of all variables and describe the sample demographics. The qualitative data comments were analysed using a thematic analysis approach incorporating organisation, familiarisation, reduction and analysis.16,17 The qualitative data were analysed independently by the research team to enhance internal validity to and to ensure concordance of themes among the research team, thereby enhancing validity of the findings.15

Results

The survey was sent electronically to 53 FDP trainees and 51 trainers. Forty-one (77.4%) and 44 (86.3%) responses were received respectively. Thirty-five (66%) responses were received from the second questionnaire sent out to the trainees, giving a total response rate of 76.6%.

The majority of trainer respondents were male (79.5%, 35) with only 20.5% (9) of respondents being female. There was a wide spread of ages of trainer respondents, ranging from under 30 to 60; of these, 68% (30) of respondents were aged between 41-60 years. The trainee respondents had a reasonably even gender split with 51.2% (21) males and 48.8% (20) females. All trainee respondents were under 41 years of age, with the majority (85.4%, 35) being under 30.

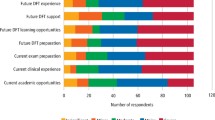

It is clear from Figure 1 that DcBDs and D-EPs were valued highly by trainees, believing them to have helped to improve their patient care. PAQs were less well regarded, however over 60% of trainees' believed them to have helped them to improve their patient care.

Case based discussions scored highly with the trainees as shown in Figure 2 with over 76.8% of trainees believing that DcBDs had helped them to improve their clinical practise. PAQs and D-EPs received a lower score, but still over 60% of trainees felt that D-EPs and PAQs had helped them in improving their patient care.

As displayed in Table 1, trainees found feedback to be extremely useful in all the WPAs (D-EPs, DcBDs and PAQs). Trainees reported feedback having a positive effect on their training by improving their confidence (>64.8%), highlighting things that they did well (>84%), through highlighting areas in which they needed to improve (>84%) and by giving them insight into their own development needs (>79.2%). Trainees (>81.6%) also felt that feedback was given in a supportive way.

The dental evaluation of performance assessment (D-EPs)

Thirty trainees (88.2%) felt that D-EPs had encouraged them to be reflective in their clinical practise and 70.7% (29) trainees agreed that the grades that they were awarded for D-EPs were an accurate reflection of their abilities.

'I believe that the D-EPs have enabled me to progress in a positive and supportive environment; they have highlighted the areas that I have progressed in and areas that may need improvement.' (Trainee Q2-14)

Fifty-seven percent of trainers felt that D-EPs were a 'very useful' or a 'vital' tool for directing learning. One of the main benefits of the D-EP process, which was commented upon by a trainer, was that the process allowed problems with trainees to be highlighted early in the year.

'It establishes a baseline of where the FD is, when he/she starts, and it allows one to pick up problems earlier than would normally occur.' (Trainer 46)

Trainers also commented that the D-EP process was a good framework in order to assist trainees to improve their skills.

'I feel that the D-EPs are an extremely valuable tool in training the trainees. We have gained a great deal from carrying out these observations and they have resulted in the trainees modifying and improving various procedures.' (Trainer 3)

Trainers also liked the format of the D-EP and that it provided a clear, easily comprehendible record to be kept throughout the year:

'The new format is very good and gives both sides elements of the assessments that are simply broken down... The competencies are straightforward to appreciate for the trainer and trainee.' (Trainer 45)

The majority of trainers (77.5%, 31) felt that the D-EP process is relevant to training. Most trainers (97.5%, 39) felt that trainees fully engaged with the D-EP process and it was a very useful tool to promote discussion and reflection with the trainees.

'A strong tool to engage reflective learning.' (Trainer 10)

The majority of trainers 82.5% (33) found the grading of 'insight' useful, in fact many trainers believe that the grading of 'insight' is not only useful for the trainees but that it is also useful for the trainer:

'Useful tool not only for the [trainee] but also the trainer. Indicates communication levels between trainee/trainer.' (Trainer 28)

'If their insight into their performance is not very good you need to go back over the stuff again until they do understand their inadequacies.' (Trainer 26)

Cased based discussion (DcBD).

Thirty-three (79.2%) trainees felt that the grades that they had been awarded for DcBDs were an accurate reflection of their abilities and 87.1% (34) of trainees felt that DcBDs encouraged them to be reflective in their clinical practise.

'Case based discussions are the best form of assessment – discussing cases with your trainer and getting feedback on how the process could have been dealt with differently was extremely helpful.' (Trainee Q2-35)

'...I found the case based discussions most useful as you were not under the pressure of performing clinically in front of someone...' (Trainee Q2-22)

Trainers felt that as a tool for directing learning DcBDs were 'very useful' (59%, 23) or 'vital' (28.2%, 11). All trainers (100%, 44) also felt that all the trainees fully engaged with the process and found the process useful:

'My trainee is keen, and finds the exercise meaningful and useful.' (Trainer 34)

Almost all (94.9%) of the trainers felt that DcBDs are relevant for training. Indeed some felt that they are essential:

'It is directly relevant to the clinical situation. From a case other issues arise, and it is a very useful learning exercise.' (Trainer 34)

Patient assessment questionnaires (PAQs)

Trainees (77.1%, 27) felt that PAQs had encouraged them to be reflective in their clinical practise and 80% (31) of trainees believed the feedback given by PAQs to be an accurate reflection of their abilities. However, there were some concer ns raised over the ambiguity and accuracy of the questions and data collected in relation to the PAQ.

'Some patients ticked all the excellent boxes as perhaps they did not want to offend or cause upset – although they were handed out by reception I wonder if some patients didn't quite think they would be completely anonymous.' (Trainee Q2-27)

'I have been told by the receptionist the patients said the PAQs are too long-winded and the fonts are too small. Hence, they just randomly tick the boxes.' (Trainee Q2-37)

Most trainers (64.8% 24) felt that PAQs are relevant to foundation training.

'We now work and live in an age of feedback and questionnaires. They are useful tools to gain insight into one's performance. Getting used to them early in one's career is sensible.' (Trainer 46)

'We are a patient-centred profession and this helps FDs realise this.' (Trainer 42)

These sentiments were supported by the trainees:

'The PAQs are probably relevant throughout the whole of a GDP's clinical career.' (Trainee Q2-34)

Respondents were asked to comment on the WPAs retrospectively towards the end of their FT year. Overall they were favourably received:

'I think workplace based assessments (D-EPs, case based discussion, PAQs) are the best type of evaluations for during your FD year, as you get direct feedback from actual patient interaction, which allows consideration of both your clinical skills but also your communication skills and professionalism.' (Trainee Q2-13)

'They all encourage open discussion, interaction with the trainer regarding clinical matters, consolidation of knowledge, and awareness of own abilities and limitations.' (Trainee Q2-8)

'I feel they are extremely relevant and help to highlight areas which may require attention. Without these highlights I would not have known which questions to ask and what else I felt I needed to know. I feel all of these assessments helped... and it's a way to improve self confidence.' (Trainee Q2-18)

However, a few of the trainees commented on the amount of time that the WPAs took and also that the associated paperwork was time consuming. Interestingly these comments were not replicated in trainers' responses. There were also comments suggesting that perhaps the amount and frequency of the WPAs should be reviewed:

'I believe that all of the forms of assessment are relevant for the whole year but instead of one per month, it might be better to do more at the beginning and less towards the end.' (Trainee Q2-26)

Discussion

This study sought the views of trainers and trainees regarding WPAs. The sample size, although small, represents approximately 5% of the total number of trainers and trainees in England. The study was confined to the Mersey Deanery foundation training scheme for ease of administration. It is accepted that there may be regional bias in the responses but the results are of value in informing the further development of FT assessment. This is a small scale local study based on WPAs in Mersey Deanery, therefore the findings may not be generalisable nationally.

The online questionnaire yielded a high response rate (76.6%), greater than would normally be expected from an online survey.15 This is possibly due to participation emails being sent from a known addressee (BG) and the ease of tracking responses and following up non-responders online.

The questionnaire results indicated a high degree of satisfaction with all the WPAs from both trainees and trainers. A study involving core medical trainees found a significant majority felt that the feedback from WPAs was useful.18 In this study trainees also valued the feedback that they received from the WPAs. Trainees felt that feedback from D-EPs (62.4%), DcBDs (76.8%) and PAQs (60.9%) helped them improve their clinical practise and improve patient care (84.1% for D-EPs, 96% for DcBDs and 60.9% for PAQs). This suggests that these tools not only helped the trainees be aware of their progress and supported experiential learning, but also had a direct perceived impact on quality of patient care and clinical practise.

Reflection is recognised as a way of thinking and a process for analysing clinical practise, enabling learning from, and development of, professional practise. There appears to be a dynamic relationship between reflective practise and self-assessment. The ability to self-assess depends upon the ability to reflect effectively on one's own practise, while the ability to reflect effectively requires accurate self-assessment.19 This is built into all the WPAs with a unique grading system of the trainee's insight and the majority of trainers thought this essential.

It is suggested that the process of reflection appears to be instrumental to feedback acceptance and is an important educational focus in the assessment and feedback process, even when there is negative feedback.20 Trainees in this study felt that feedback was provided in a supportive way and that it assisted their practise by increasing their confidence, highlighting areas in which they performed well and by providing them with insight into their own developmental needs. It is believed that feedback is a fundamental part of assessment and the facility for inclusion of 'direct and immediate feedback', preferably by positive critiquing at the end of the performance of a task, is of paramount importance in training.8

Trainers reported positively on the use of WPA tools. They felt that the tools were a clear and comprehensive record of the trainee's progress throughout the year. They believed that the real value of WPAs was the way in which they facilitated learning by highlighting any 'issues' with trainees early on, enabling them to direct learning. Trainers also felt that the WPAs were a good formalised method of encouraging and recording reflection, a requirement of the FT year.

In this study most of the trainees believed that the grades they were awarded for the WPAs were an accurate reflection of their abilities and therefore a fair assessment tool (D-EPs 70.7%, DcBDs 79.2%, PAQs 80%). A study of WPAs in medicine found similar positive responses.13

A minority of trainees commented on the data collected through the PAQ, questioning its validity. Conversely 80% of trainees believed the feedback given by PAQs to be an accurate reflection of their abilities. This conflicting data requires further investigation with a possibility of re-designing the PAQs and providing strict guidelines for their distribution. A recent study reported multisource feedback from professional colleagues and patient feedback on consultations to be most likely to offer a reliable and feasible opinion of clinical performance.12

A small number of trainees also made comments suggesting that the number and regularity of the WPAs should be reviewed. However these sentiments were not supported by the trainers who felt that the WPAs were relevant to the whole FT year (D-EPs 77.5%, DcBDs 94.9%, PAQs 64.8%).

Conclusions

The results from this study indicate that the experience of WPAs is extremely positive and that they have a significant role in the trainee's experiential learning. The most significant contribution to professional development and improvement of patient care comes from the direct feedback and reflection as a result of completing WPAs.

The study clearly highlights the effectiveness of WPAs in dental foundation training and will, in conjunction with the rest of the dental foundation portfolio, help demonstrate many of the competencies in the dental foundation training curriculum and will contribute to the satisfactory completion of FT in England. The aim of the DFT curriculum is to produce a competent, caring, reflective practitioner and this study clearly demonstrates how the use of WPAs in dental FT within a portfolio of evidence contributes significantly to achieving this aim.

References

The National Health Service (Performers Lists) Regulations 2005. Statutory Instrument 2005 No. 3491. London: The Stationery Office, 2005.

Grieveson B. Assessment in dental vocational training... can we do better? Br Dent J 2002; 193 (Suppl): 19–22.

Palmer N O, Grieveson B . An investigation of trainers' and VDPs' views in the Mersey Deanery of the FGDP(UK) Key Skills in Primary Dental Care and assessment of vocational training. Prim Dent Care 2008; 15: 5–10.

Committee of Postgraduate Dental Deans and Directors. A curriculum for UK Dental Foundation Programme training. London. Department of Health, 2006. Available from http://www.copdend.org.uk.

Committee of Postgraduate Dental Deans and Directors. Dental foundation training professional development portfolio. London: COPDEND, 2009. Available from http://www.copdend.org.uk.

Archer J C. State of the science in health professional education: effective feedback. Med Educ 2010; 44: 101–108.

Embo M P C, Driessen E W, Valcke M, Van der Vleuten C P M . Assessment and feedback to facilitate self-directed learning in clinical practice of midwifery students. Med Teach 2010; 32: e263–e269.

Oliver R, Kersten H, Vinkka-Puhakka H et al. Curriculum structure: principles and strategy. Eur J Dent Educ 2008; 12 (Suppl 1): P74–P84.

Norcini J, Burch V . Workplace based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Med Teach 2007; 29: 855–871.

Veloski J, Boex J R, Grasberger M J et al. Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and physicians' clinical performance: BEME Guide No. 7. Med Teach 2006; 28: 117–128.

Ashley F A, Gibson B, Daly B, Baker S, Newton J T . Undergraduate and postgraduate dental students' 'reflection on learning': a qualitative study. Eur J Dent Educ 2006; 10: 10–19.

Murphy D J, Bruce D A, Mercer S W, Eva K W . The reliability of workplace-based assessment in postgraduate medical education and training: a national evaluation in general practice in the United Kingdom. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009; 14: 219–232.

Wilkinson J R, Crossley J G M, Wragg A, Mills P, Cowan G, Wade W . Implementing workplace based assessments across the medical specialties in the United Kingdom. Med Educ 2008; 42: 364–373.

Prescott L, Hurst Y, Rennie J S . Comprehensive validation of competencies for dental vocational training and general professional training. Eur J Dent Educ 2003; 7: 154–159.

Cohen L, Manion M, Morrison K . Research methods in education. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Polit D F, Beck C T . Essentials of nursing research: appraising evidence for nursing practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott William & Wilkins, 2009.

Miles M B, Huberman A M . Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. California: Sage Publications, 1994.

Johnson G l, Barnett J, Jones M, Wade W . Feedback from educational supervisors and trainees on the implementation of curricula and assessment system for core medical trainees. Clin Med 2008; 8: 484–489.

Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A . Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009; 14: 595–621.

Sargeant J M, Mann K V, Van der Vleuten C P, Metsemakers J F . Reflection: a link between receiving and using assessment feedback. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009; 14: 399–410.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the funding for this project which was awarded by COPDEND in 2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grieveson, B., Kirton, J., Palmer, N. et al. Evaluation of workplace based assessment tools in dental foundation training. Br Dent J 211, E8 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.681

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.681

This article is cited by

-

Using live stream technology to conduct workplace observation assessment of trainee dental nurses: an evaluation of effectiveness and user experience

BDJ Open (2023)

-

An evaluation of civilian and military dental foundation training

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Workplace-based assessment: a review of user perceptions and strategies to address the identified shortcomings

Advances in Health Sciences Education (2016)

-

A national evaluation of workplace-based assessment tools (WPBAs) in foundation dental training: a UK study. Effective and useful but do they provide an equitable training experience?

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

An explanation of workplace-based assessments in postgraduate dental training and a review of the current literature

British Dental Journal (2013)