Abstract

Malnutrition in patients with cancer is common and an adverse prognostic indicator. A questionnaire answered by 357 (72%) UK specialist oncological trainees suggests that they lack the ability to identify factors that place patients at risk from malnutrition. Major barriers to effective nutritional practice included lack of guidelines, knowledge and time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

As long ago as 1932, malnutrition was identified as a prognostic indicator of the outcome in cancer patients (Warren, 1932). Up to 80% of patients with cancer are malnourished at presentation (Dewys et al, 1980; O’Gorman et al, 1998), and in up to 20%, malnutrition is a significant contributing factor to their death (Ottery, 1996). Studies show poorer response to treatment, a reduced quality of life and increased risk of death in those patients who have lost weight (Oveson et al, 1993; Andreyev et al, 1998; Ross et al, 2004).

Best practice, as stated by NICE Guidelines requires that patients should undergo nutritional assessment so that those shown to be at risk can be considered for treatment (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2006). The publication Nutrition and patients: a doctor's responsibility (Kopelman and Lennard-Jones, 2002) set out to raise awareness of the fundamental importance of nutritional care in everyday clinical practice. Yet, there is overwhelming evidence to suggest that few doctors deal with malnutrition adequately (McWhirter and Pennington, 1994; Edington et al, 2000; Kelly et al, 2000; Beck et al, 2002). An understanding of health professionals’ attitudes to nutrition, particularly those of oncologists who look after patients with the highest prevalence of malnutrition, is important if it is to be recognised efficiently and steps taken to address it.

The aims of the study were three-fold: to develop an understanding of the extent to that oncologists are able to identify malnutrition, to elucidate the importance which oncologists place on nutrition as a variable in the clinical care and outcome of their patient and to identify the barriers that might exist in the decision to advocate nutritional support.

Materials and methods

A case-scenario-based questionnaire was developed and piloted to address three issues: (1) the identification of malnutrition, (2) the importance of nutritional status and support and (3) the barriers preventing nutritional intervention. Two case scenarios in patients with gastrointestinal cancer were used, the first related to identification of malnutrition and the second to the role and indication for nutritional support for a patient who had lost weight. Additionally, their views on the importance of various factors in treatment outcome and confidence in assessing malnutrition were assessed.

The final version of the questionnaire was piloted in all specialist oncological trainees at one centre. Subsequently, on the basis of the responses recorded, it was decided to send it out to all UK trainees, identified by their membership of the Association of Cancer Physicians, UK or the Royal College of Radiologists, UK. The scenarios were content validated by a group of defined UK experts on malnutrition, who set the expert standard.

Results were analysed using SPSS v13. Frequencies were described and χ2 tests were used to assess whether there were associations between nutritional practice, knowledge and attitudes and clinical speciality, nutritional education or years of clinical and oncology experience. Significance was established at P<0.05.

Results

Between April and June 2003, 61 pilot questionnaires were distributed to trainees in one institution. Subsequently, between September 2004 and April 2005, a further 433 questionnaires were sent out to all trainees in the UK. Of 494 questionnaires in total, 357 were returned (72% response rate). Of these, six were not completed because the recipient was no longer working in oncology, and 14 because they were not available at the given address. Of the 337 completed, the maximum missing data for any scenario response on completed questionnaires was less than 2% (n<7). Nineteen questionnaires were sent out to experts, of whom 16 replied (84%). The characteristics of the responders are shown in Table 1.

Do oncologists consider nutrition important to outcome?

Almost all specialist oncological trainees thought that ‘stage’ or ‘performance status’ was very important to the outcome, but nearly two-thirds (65%, n=217) rated nutritional status as very important. Age and patient attitude were rated as much less important (Table 2a).

In the case study scenario, nearly all trainees thought that the patient's morbidity and quality of life would be affected by nutritional intervention. A substantial majority also felt that nutrition intervention would play a role in hospital stay (76%, n=255) and treatment toxicity (78%, n=261), but a larger number indicated uncertainty. Trainees were least likely to agree that nutritional intervention would play a role in mortality with regard to this patient (Table 2b).

Can oncologists identify malnutrition?

The majority of specialist oncological trainees (80%, n=267) expressed uncertainty or a lack of confidence in their ability to identify malnutrition. Those who had undergone undergraduate nutritional lectures were more confident (P<0.01), but no association was found between confidence and speciality (medical vs clinical oncologist) age, medical or oncological experience or type of hospital was seen.

There was a discrepancy (Table 3a) between trainees who significantly more frequently identified the case patient as definitely malnourished in comparison to experts (P<0.05).

When asked which variables they would find useful to assess nutritional status (Table 3b), 48% (n=160) of trainees failed to specify height and/or body mass index. Just over one-quarter of trainees identified the additional variables necessary to identify risk according to the Malnutrition Advisory Guidelines (MAG), Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (‘MUST’) criteria or the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST), compared to over three-quarters of experts. A similar pattern was shown by trainees (29%, n=97), in recording half or more of the six variables required to identify nutritional risk according to the Patient Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA), a specific and validated tool for assessing cancer patients’ nutritional status. The ability of oncologist trainees to identify relevant variables was associated with undergraduate nutrition lectures (P<0.05) but not with medical or oncological experience.

When asked to identify the level of weight loss in a 1-month period, which indicated that nutritional intervention was necessary (Table 3c; case scenario 2), again specialist oncological trainees gave significantly different replies to experts (P<0.05), who considered nutritional intervention as necessary at a lower level of weight loss than the trainees.

What barriers prevent inclusion of nutrition in oncologist patient care?

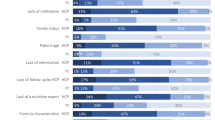

As shown in Table 4, the three principal barriers to nutritional intervention by specialist oncological trainees were reported to be lack of clear guidelines (n=231, 69%), lack of knowledge (n=201, 60%) and lack of time (n=188, 56%). Two hundred and seventy (80%) oncological trainees wanted additional training in this area.

Discussion

The study suggests that oncologist trainees accept that nutritional status and nutritional intervention are important to outcome in patients receiving active therapy for malignancy. However, there is an inability to identify patients at risk of malnutrition and to refer those who may benefit from early nutritional intervention. Further barriers include a lack of recognised guidelines as to when to recommend nutritional intervention for weight loss.

Timely and appropriate interventions for patients with cancer require adoption of routine nutritional screening and evaluation (Ottery, 1995). Yet, hospital surveys suggest nutritional risk screening and assessment as part of routine practice is generally not performed (Duncan and Silk, 1997; Kondrup et al, 2002). It has been shown that malnutrition is largely unrecognised by health professionals (Edington et al, 2000). Similar findings more recently have come from The Council of Europe Group survey on nutritional care in European hospitals (Beck et al, 2002). Our study suggests that these findings on generalised hospital populations are also relevant in the oncological setting. This is particularly important as oncological treatment is increasingly given in the ‘outpatient’ setting where any standard ward-based nutrition assessment tool is not typically used. This study suggests that oncology trainees fail to identify patients appropriately for nutritional assessment, not because they think it is unimportant but rather because of lack of ability, confidence and knowledge of important criteria, which should determine effective nutritional practice.

There are limitations inherent in the questionnaire as a method of survey. Ideally, stringent methods of validation and reliability testing are required. However, our questionnaire was developed after a pilot study. This study is also limited in that it addresses the outcome at which behaviour is directed rather than the actual behaviour. Further research would need to ascertain actual rather than reported nutrition practice.

The study suggests that future research also needs to be directed at the best method of providing effective, concise and relevant nutritional education interventions to oncologist trainees.

In conclusion, oncologists lack the ability to identify factors that place patients at risk from malnutrition. Although oncologists acknowledge the importance of nutritional support, barriers such as lack of knowledge, clear guidelines and lower priority because of time constraints may prevent referral for, or direct nutritional intervention. Until the ethos of optimal nutritional management is strengthened in clinical practice, probably through continuing effective education and training at all levels within the medical profession, the rate of untreated malnutrition may remain unacceptably high and continue to compromise patient outcomes.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Andreyev HJN, Norman AR, Oates J, Cunningham D (1998) Why do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy? Eur J Cancer 34: 503–509

Beck AM, Balknas UN, Camilo ME, Furst P, Gentile MG, Hasunen K, Jones L, JonkersSchuitema C, Keller U, Melchior JC, Mikkelsen BE, Pavcic M, Schauder P, Sivonen L, Zinck O, Oien H, Ovesen L (2002) Practices in relation to nutritional care and support – report from the Council of Europe. Clin Nutr 2: 351–354

Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, Band PR, Bennett JM, Bertino JR, Cohen MH, Douglass Jr HO, Engstrom PF, Ezdinli EZ, Horton J, Johnson GJ, Moertel CG, Oken MM, Perlia C, Rosenbaum C, Silverstein MN, Skeel RT, Sponzo RW, Tormey DC (1980) Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Med 69: 491–497

Duncan HD, Silk DB (1997) Diagnosis and treatment of malnutrition. J R Coll Physicians Lond 31: 497–502

Edington J, Boorman J, Durrant ER, Perkins A, Giffin CV, James R, Thomson JM, Oldroyd JC, Smith JC, Torrance AD, Blackshaw V, Green S, Hill CJ, Berry C, McKenzie C, Vicca N, Ward JE, Coles SJ (2000) Prevalence of malnutrition on admission to four hospitals in England. The Malnutrition Prevalence Group. Clin Nutr 19: 191–195

Kelly IE, Tessier S, Cahill A, Morris SE, Crumley A, McLaughlin D, McKee RF, Lean ME (2000) Still hungry in hospital: identifying malnutrition in acute hospital admissions. QJ Med 93: 93–98

Kondrup J, Johansen N, Plum LM, Bak L, Larsen IH, Martinsen A, Andersen JR, Baernthsen H, Bunch E, Lauesen N (2002) Incidence of nutritional risk and causes of inadequate nutritional care in hospitals. Clin Nutr 21: 461–468

Kopelman P, Lennard-Jones J (2002) Nutrition and patients: a doctor's responsibility. Clin Med 2: 391–394

McWhirter JP, Pennington CR (1994) Incidence and recognition of malnutrition in hospital. BMJ 308: 945–948

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2006) Nutrition Support in Adults. Clinical Guideline 32. London: NICE

O’Gorman P, McMillan DC, McArdle CS (1998) Impact of weight loss, appetite, and the inflammatory response on quality of life in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Nutr Cancer 32: 76–80

Ottery FD (1995) Supportive nutrition to prevent cachexia and improve quality of life. Semin Oncol 22: 98–111

Ottery FD (1996) Definition of standardized nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition 12: S15–S19

Oveson L, Hannibal J, Mortensen EL (1993) The interrelation of weight loss, dietary intake and quality of life in ambulatory patients with cancer of the lung breast and ovary in cancer patients. Nutr Cancer 19: 159–167

Ross PJ, Ashley S, Norton A, Priest K, Waters JS, Eisen T, Smith IE, O’Brien ME (2004) Do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancers? Br J Cancer 90: 1905–1911

Warren S (1932) The immediate cause of death in cancer. Am J Med Sci 184: 610–613

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following for their expert contribution: Rodney Burnham, Jackie Edington, Marinos Elia, Ken Fearon, Gary Frost, Alastair Forbes, Simon Gabe, Robert Grimble, Alan Jackson, Derek Macallan, Jeremy Nightingale, Jeremy Powell-Tuck, David Silk, Rebecca Stratton, Mike Stroud and Rick Wilson. We would also like to thank Lorraine Davis for her administrative support. This study was supported by funds provided by the Trustees of the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, UK. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to declare. This study was discussed with the Chairman of the Research and Ethics committees of the Royal Marsden Hospital and considered not to require ethical approval.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Spiro, A., Baldwin, C., Patterson, A. et al. The views and practice of oncologists towards nutritional support in patients receiving chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 95, 431–434 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603280

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603280