- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Judith S. L. Partridge, Geraint Collingridge, Adam Lee Gordon, Finbarr C. Martin, Danielle Harari, Jugdeep K. Dhesi, Where are we in perioperative medicine for older surgical patients? A UK survey of geriatric medicine delivered services in surgery, Age and Ageing, Volume 43, Issue 5, September 2014, Pages 721–724, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu084

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Introduction: national reports have highlighted deficiencies in care provided to older surgical patients and suggested a role for innovative, collaborative, inter-specialty models of care. The extent of geriatrician-led perioperative services in the UK (excluding orthogeriatric services) has not previously been described. This survey describes current services and explores barriers to further development.

Methods: an electronic survey was sent to clinical leads for geriatric medicine at all 161 acute NHS health care trusts in the UK. Reminders were sent on three occasions over an 8-week period. The survey examined preoperative and postoperative care and organisational issues. Responses were analysed descriptively.

Results: there were 130 respondents (80.7%). One-third (38) of respondents described providing some geriatric medicine input in older surgical patients. Preoperative services existed in 15 (12%), where 14 provided risk assessment and 13 preoperative optimisation. Twenty-six respondents (20%) delivered care postoperatively, of them 10 took a reactive approach, 11 a proactive approach and 5 provided a combination of reactive and proactive care. Barriers to establishing perioperative geriatric medicine services included funding, workforce issues and a lack of inter-specialty collaboration.

Conclusion: a national appetite exists to provide geriatrician-led services to older surgical patients yet the majority of existing services remain reactive and do not use comprehensive geriatric assessment as an organising principle. This survey suggests that funding for geriatricians in perioperative care has not yet been universally established. Future efforts should focus on dissemination of experiential knowledge and published resources, collaboration with commissioners and empirical research to overcome the barriers described.

Introduction

Despite recent advances in surgical and anaesthetic techniques, older people undergoing both elective and emergency surgery continue to experience excess adverse postoperative outcomes compared with younger patients [1]. Adverse outcomes have been attributed to age-related physiological change, multimorbidity [2] and the prevalence of geriatric syndromes [3, 4]. There has been recent focus on establishing effective clinical pathways to ensure that evidence-based methods are used to risk assess and optimise patients perioperatively, with UK national reports recommending routine daily input from geriatric medicine teams for older patients undergoing surgery [5]. It has been recognised that the contribution of geriatricians is likely to involve evaluation and management of risk, promoting shared decision-making and co-ordinating the inputs of a multidisciplinary team [6].

Outside the surgical context, geriatricians have improved patient-related outcomes by undertaking comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), defined as a multidimensional interdisciplinary diagnostic process focused on determining a frail elderly person's medical, psychological and functional capability to develop a coordinated and integrated plan for treatment and long-term follow-up [7]. CGA has a strong evidence base in acute hospital [8] and community care settings [9]. If geriatricians are to improve outcomes in older surgical patients, it is likely that this will also be through CGA [10].

To enable future service development and research about perioperative geriatric medicine, this survey aimed to establish

Whether geriatrician-led services exist for older surgical patients within the UK?

What geriatrician-led perioperative services consist of and how they are funded?

What geriatricians perceive as the barriers to the future development of such services?

Methods

The survey (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix 1) consisted of 18 questions, divided into three main sections; preoperative care, postoperative care and organisational information. The survey content was based on themes identified through national reports and best practice guidelines [5, 6, 11–14]. Questions used a combination of multiple choice, ranking and Likert formats. The survey was reviewed for readability, non-ambiguity and content validity by 10 expert clinicians experienced in the perioperative management of older people. The overall content validity ratio was 0.66, above the validity threshold of 0.62 for 10 expert raters [15].

Participants were identified through a comprehensive list of clinical leads for geriatric medicine at all UK trusts held by the British Geriatrics Society. All were sent an email with a weblink to an electronic version of the survey. Non-respondents were contacted again at 2, 4 and 6 weeks with a further invitation to participate. Responses were analysed using basic descriptive statistics and reported by themes.

Results

Provision of geriatric medicine clinical care for surgical patients

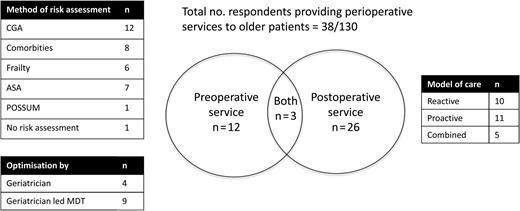

Responses were received from 130 of 161 trusts undertaking emergency and elective surgery, a response rate of 80.7%. Thirty-eight respondents (29.2%) provided geriatric medicine input into the care of older surgical patients. The variety in clinical services provided by geriatricians to the older surgical population is represented in Figure 1.

Features of perioperative services provided by geriatric medicine in the UK.

Of the 38 trusts providing a service, 15 did so preoperatively, with focus on risk assessment in 14 trusts and medical optimisation in 13. Twelve trusts described CGA as the principle guiding preoperative assessment.

Of those trusts focussing on risk assessment, six used tools quantifying frailty and eight used anaesthetic perioperative risk-assessment tools as a routine part of preoperative assessment (American Society of Anaesthesiologists Score [16] in seven and physiological and operative severity score for the enumeration of mortality and morbidity (POSSUM) score [17] in one trust).

Of those trusts focussing on preoperative optimisation, nine used a geriatrician-led multidisciplinary team (MDT), whereas four used a geriatrician without an MDT.

Twenty-six trusts (68.4%) provided postoperative geriatric medicine input. This was provided following elective procedures in 14 and emergency surgery in 24. Ten trusts used ‘reactive’ models of care, where geriatricians attended following referrals from the surgical team, while 11 provided ‘proactive’ models, incorporating some component of active case-finding by geriatricians. A combined approach was taken in five trusts. When asked to reflect on the last surgical patient who they saw, geriatricians reported providing a variety of services (Table 1).

Components of perioperative services for older surgical patients

| Clinical service provided . | No respondents . |

|---|---|

| Postoperative medical management | 18 |

| Rehabilitation and goal setting | 18 |

| Discharge planning | 15 |

| Setting ceilings of care | 13 |

| Sanctioning move to geriatric medicine bed | 11 |

| Preoperative medical management | 10 |

| Sanctioning move to community rehabilitation facility | 8 |

| Assessment of capacity | 7 |

| Clinical service provided . | No respondents . |

|---|---|

| Postoperative medical management | 18 |

| Rehabilitation and goal setting | 18 |

| Discharge planning | 15 |

| Setting ceilings of care | 13 |

| Sanctioning move to geriatric medicine bed | 11 |

| Preoperative medical management | 10 |

| Sanctioning move to community rehabilitation facility | 8 |

| Assessment of capacity | 7 |

Components of perioperative services for older surgical patients

| Clinical service provided . | No respondents . |

|---|---|

| Postoperative medical management | 18 |

| Rehabilitation and goal setting | 18 |

| Discharge planning | 15 |

| Setting ceilings of care | 13 |

| Sanctioning move to geriatric medicine bed | 11 |

| Preoperative medical management | 10 |

| Sanctioning move to community rehabilitation facility | 8 |

| Assessment of capacity | 7 |

| Clinical service provided . | No respondents . |

|---|---|

| Postoperative medical management | 18 |

| Rehabilitation and goal setting | 18 |

| Discharge planning | 15 |

| Setting ceilings of care | 13 |

| Sanctioning move to geriatric medicine bed | 11 |

| Preoperative medical management | 10 |

| Sanctioning move to community rehabilitation facility | 8 |

| Assessment of capacity | 7 |

Collaboration with other perioperative specialties

Only 20 respondents had spoken at surgical and 7 at anaesthetic audit meetings within their trust in the past year. For those who had presented, 20 respondents had presented once, 6 had presented twice and a single respondent three or more times. Twenty-two trusts had involved geriatricians in writing local clinical guidelines for older surgical patients. In the majority of cases, these covered delirium.

Organisational factors and perceived barriers to development of services

Fifty-four trusts did not provide dedicated funding to deliver geriatric medicine services to older surgical patients. A further 22 provided perioperative geriatric medicine input from within the operating budgets of geriatric medicine departments. For those trusts with ring-fenced funding for perioperative geriatrics, 13 provided this from the medical directorate, 5 from combined medical and surgical budgets and 9 from surgical directorates.

Where ring-fenced funding existed, this was predominantly used for consultant sessions (27 respondents), with eight trusts funding specialist registrar sessions and seven funding junior medical staff. Allied health professionals (AHPs) were also funded (clinical nurse specialist 10, physiotherapy 11, occupational therapy 13, and social worker 8). In some hospitals, AHP support was provided by extending the roles of existing falls, Parkinson's disease and Older Persons Liaison clinical specialists [18].

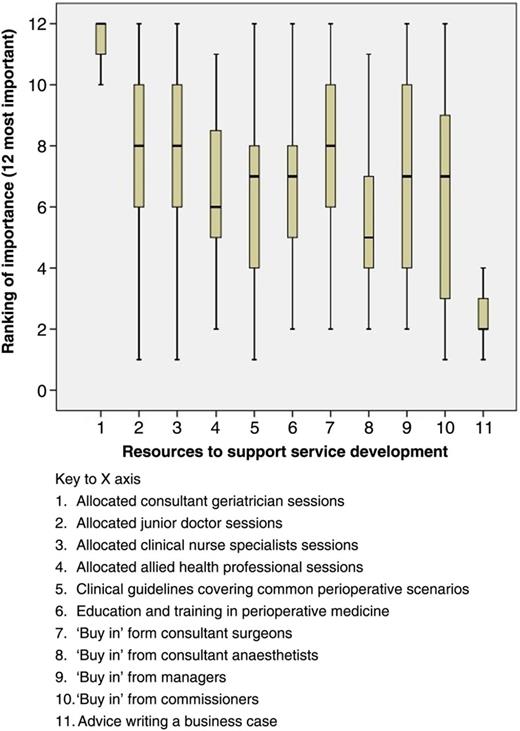

Barriers to the development of perioperative services for older surgical patients were explored by asking respondents to rank the importance of potential resources in expanding their services, with responses summarised in Figure 2.

Respondents’ views on what would help them to further develop perioperative services for older surgical patients.

Discussion

This is the first UK-wide survey examining the role of geriatricians in perioperative services for older surgical patients and shows that about a third of respondents offer such services. Only a small proportion of them explicitly recognise CGA as a guiding principle, despite the compelling evidence from other settings that the use of CGA improves clinical outcomes. The majority of respondents provided only postoperative services, did so reactively and focussed on emergency cases. This is contrary to emerging evidence that early proactive multidisciplinary CGA and optimisation can improve postoperative outcomes in older patients [10] and the weight of evidence from orthogeriatrics, suggesting that proactive services deliver better outcomes [19].

In the majority of trusts, geriatricians were not fully engaged as members of the perioperative team, with limited involvement in surgical and anaesthetic meetings and in the development of guidelines relevant to older surgical patients.

It is noteworthy that the majority of respondents cited funding difficulties as a barrier to establishing perioperative geriatric medicine services. The fact that only a minority received funding from surgical directorates suggests that the case for geriatricians and CGA may not be widely accepted outside our specialty.

The difficulty in recruiting geriatricians into perioperative medicine consultant posts reflects the mismatch between the demand for geriatricians and the number of specialists emerging from training. One way of bridging this gap would be to employ more nurse specialists to provide perioperative services for older people, yet this survey identified only 10 such posts across the UK.

The limitations of this study are those inherent in all surveys. There was the possibility of response bias; trusts with surgical liaison services may have been more likely to respond, resulting in over-representation. Potential ambiguity in interpretation of questions and therefore in response exists and it was not possible to interrogate responses in greater detail from an anonymous survey. However, the response rate was high for an online questionnaire [20], and the work we undertook to establish face and content validity went some way to addressing these concerns.

In conclusion, this survey demonstrates that the involvement of geriatricians in perioperative care of older people in the UK remains limited. Most services are reactive and oligodisciplinary, despite evidence from other settings that geriatricians are most effective when their care is proactive and delivered as part of a multidisciplinary team.

The difficulty in establishing funding suggests that the case for CGA in perioperative care may not be widely accepted outside our specialty. This may be addressed by dissemination of current good practice guidance [12–14, 21] and by addressing the paucity of empirical evidence regarding the effectiveness and translation of CGA into clinical pathways for older surgical patients.

Adverse postoperative outcomes in older surgical patients can be due to inadequate management of perioperative risks.

Surgeons, anaesthetists and geriatricians should work collaboratively to develop pathways of care for older surgical patients.

This survey demonstrates enthusiasm from UK geriatricians to develop and lead such innovative services.

Despite this fewer than a third of UK geriatric medicine departments provide such a service.

Using published resources, research and collaboration with commissioners may overcome existing funding and workforce barriers.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Comments