Abstract

BACKGROUND: Providing and eliciting high-quality feedback is valuable in medical education. Medical learners’ attainment of clinical competence and professional growth can be facilitated by reliable feedback. This study’s primary objective was to identify characteristics that are associated with physician teachers’ proficiency with feedback.

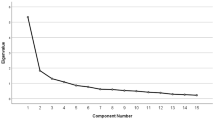

METHODS: A cohort of 363 physicians, who were either past participants of the Johns Hopkins Faculty Development Program or members of a comparison group, were surveyed by mail in July 2002. Survey questions focused on personal characteristics, professional characteristics, teaching activities, self-assessed teaching proficiencies and behaviors, and scholarly activity. The feedback scale, a composite feedback variable, was developed using factor analysis. Logistic regression models were then used to determine which faculty characteristics were independently associated with scoring highly on a dichotomized version of the feedback scale.

RESULTS: Two hundred and ninety-nine physicians responded (82%) of whom 262 (88%) had taught medical learners in the prior 12 months. Factor analysis revealed that the 7 questions from the survey addressing feedback clustered together to form the “feedback scale” (Cronbach’s α: 0.76). Six items, representing discrete faculty responses to survey questions, were independently associated with high feedback scores: (i) frequently attempting to detect and discuss the emotional responses of learners (odds ratio [OR]=4.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2 to 9.6), (ii) proficiency in handling conflict (OR=3.7, 95% CI 1.5 to 9.3), (iii) frequently asking learners what they desire from the teaching interaction (OR=3.5, 95% CI 1.7 to 7.2), (iv) having written down or reviewed professional goals in the prior year (OR=3.2, 95% CI 1.6 to 6.4), (v) frequently working with learners to establish mutually agreed upon goals, objectives, and ground rules (OR=2.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.7), and (vi) frequently letting learners figure things out themselves, even if they struggle (OR=2.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.9).

CONCLUSIONS: Beyond providing training in specific feedback skills, programs that want to improve feedback performance among their faculty may wish to promote the teaching behaviors and proficiencies that are associated with high feedback scores identified in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Available at: http://www.britannica.com. Accessed February 22, 2004.

Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250:777–81.

Gorn MH. Expanding the Envelope: Flight Research at NACA and NASA. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky; 2001.

Nadler DA. Feedback and Organization Development: Using Data-Based Methods. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Inc.; 1977.

Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Acad Med. 2004;79(suppl 10):S70-S81.

Crowley RS, Naus GJ, Stewart J, Friedman CP. Development of visual diagnostic expertise in pathology: an information-processing study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:39–51.

Horiszny JA. Teaching cardiac auscultation using simulated heart sounds and small group discussion. Fam Med. 2001;33:39–44.

Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, McGaghie WC, et al. Effectiveness of computer-based system to teach bedside cardiology. Acad Med. 1999;74(suppl 10):S93-S5.

Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, McGaghie WC, et al. Effectiveness of a cardiology review course for internal medicine residents using simulation technology and deliberate practice. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14:223–8.

McGuire C, Hurley RE, Babbott D, Butterworth JS. Auscultatory skill: gain and retention after intensive instruction. J Med Educ. 1964;39:120–30.

Wigton RS, Patil KD, Hoellerich VL. The effect of feedback in learning clinical diagnosis. Acad Med. 1986;61:816–22.

Schwartz S, Griffin T. Comparing different types of performance feedback and computer-based instruction in teaching medical students how to diagnose acute abdominal pain. Acad Med. 1993;68:862–4.

Ende J. The evaluation product: putting it to use. In: Lloyd JS, Langsley DG, eds. How to Evaluate Residents. Chicago: American Board of Medical Specialties; 1986:99–116.

Corley JB. Evaluating Residency Training. Lexington, MA: The Collamore Press; 1983.

Kogan JR, Bellini LM, Shea JA. Have you had your feedback today? Acad Med. 2000;75:1041.

Gil DH, Heins M, Jones PB. Perceptions of medical school faculty members and students on clinical clerkship feedback. J Med Educ. 1984;59:856–64.

Robins LS, Gruppen LD, Alexander GL, Fantone JC, Davis WK. A predictive model of student satisfaction with the medical school learning environment. Acad Med. 1997;72:134–9.

Clark JM, Houston TK, Kolodner K, Branch WT, Levine RB, Kern DE. Teaching the teachers: national survey of faculty development in departments of medicine of U.S. teaching hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:205–14.

Cole KA, Barker LR, Kolodner K, Williamson PR, Wright SM, Kern DE. Faculty development in teaching skills: an intensive longitudinal model. Acad Med 79:469–80.

Skeff KM, Stratos GA, Mygdal WK, et al. Clinical teaching improvement: past and future for faculty development. Fam Med. 1997;29:252–7.

Knight AM, Cole KA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Long-term follow up of a longitudinal faculty development program in teaching skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:721–5.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Wiley; 1989.

Nunnaly J. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978.

Kravas CF, Kravas KJ. Effective feedback principles sheet. In: Thayer L, ed. 50 Strategies for Experiential Learning: Book One. San Diego: University Associates Inc.; 1976:148.

Wallace L. Non-evaluative approaches to performance appraisals. Supervisory Management; MAR 1978:97–101.

Feins A, Waterman MA, Peters AS, Kim M. The teaching matrix: a tool for organizing teaching and promoting professional growth. Acad Med. 1996;71:1200–3.

Orlander JD, Bor DH, Strunin L. A structured clinical feedback exercise as learning-to-teach practicum for medical residents. Acad Med. 1994;69:18–20.

Porter L. Giving and Receiving Feedback; It Will Never Be Easy, But It Can Be Better. NTL Reading Book for Human Relations Training. Alexandria, VA: NTL Institute; 1982.

Irby DM. What clinical teachers in medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69:333–42.

Westberg J, Jason H. Providing Constructive Feedback: A CIS Guide Book for Health Profession Teachers. Boulder, CO: Center for Instructional Support, Johnson Printing; 1991.

Kern DE, Wright SM, Carrese JA, et al. Personal growth in medical faculty: a qualitative study. West J Med. 2001;175:98.

Wilkerson L, Irby DM. Strategies for improving teaching practices: a comprehensive approach to faculty development. Acad Med. 1998;73:387–96.

Irby DM, Gillmore GM, Ramsey PG. Factors affecting ratings of clinical teachers by medical students and residents. J Med Educ. 1987;62:1–7.

Henderson P, Ferguson-Smith AC, Johnson MH. Developing essential professional skills: a framework for teaching and learning about feedback. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:11.

Ludmerer KM. Learner-centered medical education. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1163–4.

Gunderman RB, Williamson KB, Frank M, Heitkamp DE, Kipfer HD. Learner-centered education. Radiology. 2003;227:15–7.

Wolpaw TM, Wolpaw DR, Papp KK. Snapps: a learner-centered model for outpatient education. Acad Med. 2003;78:893–8.

Pinsky LE, Monson D, Irby DM. How excellent teachers are made: reflecting on success to improve teaching. Adv Health Sci Educ. 1998;3:207–15.

Pinsky LE, Irby DM. If at first you don’t succeed: using failure to improve teaching. Acad Med. 1997;72:973–6.

Thayer L. 50 Strategies for Experiential Learning: Book One. San Diego, CA: University Associates Inc.; 1976.

Levy D. Regular feedback holds the key to improving house staff performance. Careers Intern Med. 1985;1:38–40.

Torre DM, Sebastian JL, Simpson DE. Learning activities and high-quality teaching: perceptions of third-year IM clerkship students. Acad Med. 2003;78:812–4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Dr. Wright is an Arnold P. Gold Foundation Associate Professor of Medicine. The authors are indebted to Dr. L. Randol Barker, Dr. David Kern, Ms. Cheri Smith, and Ms. Darilyn Rohlfing for their assistance.

Financial Support: The Johns Hopkins Faculty Development Program in Teaching Skills is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration, Grant #5 D55HP00049-05-00.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Menachery, E.P., Knight, A.M., Kolodner, K. et al. Physician characteristics associated with proficiency in feedback skills. J GEN INTERN MED 21, 440–446 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00424.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00424.x