Abstract

Clinical scenario

A 54 year-old man consults about a long-standing cough: his wife encouraged him to attend as she was tired of hearing him cough all the time. He is a bit vague about when it started, but it must be ‘nearly a year’. He has consulted his usual general practitioner about the cough three times. Eight months ago he presented with a ‘chesty’ cough associated with a feverish illness and an upper respiratory tract infection; he was prescribed a course of antibiotics which he thinks might have slightly improved the cough, though it did not fully resolve. Two subsequent consultations resulted in a further course of antibiotics and a trial of a salbutamol inhaler, neither of which appear to have made any difference. The clinical notes record that his chest was ‘clear’ at each of these consultations. He describes himself as ‘generally well’, though he has been tired recently which he attributes to the long hours he is working. He smoked for about 15 years but quit in his mid-thirties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Drugs have the potential to cause a myriad of respiratory syndromes: here we consider specifically drug-induced cough. It is important to recognise that cough may be the initial manifestation of more serious drug-induced pulmonary syndromes such as interstitial lung disease, acute lung injury, pleural disease and pulmonary vascular disease caused by a number of well-recognised drugs (amiodarone, nitrofurantoin, methotrexate to name a few) which are not considered here. For more extensive reviews and an online drug database of pneumotoxicities which can be a useful reference of described toxicities if in doubt, see www.pneumotox.com.1,2 This short paper will consider the commonly used drugs that may be implicated in chronic cough.

ACE inhibitors

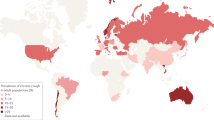

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors cause dry nocturnal cough in about 5–35% of people. Release of bradykinin, which is normally metabolised by ACE in the lungs, results in a typical tickling, scratchy or itchy sensation in the throat.3 There is a poor dose-response relationship and it normally occurs within the first week of treatment — but onset can sometimes be delayed for up to six months. In addition, although most cases subside after four weeks, a significant proportion of cases can take up to three months to resolve after stopping the drug.4 Although theophylline and cromoglycate have been advocated in the past to treat this cough, the only effective treatment is stopping the drug. It is more common in women (perhaps due to the heightened cough reflex in women) and also, interestingly, in Chinese people.5 Airflow obstruction is not usually a feature, and the presence of asthma does not change the likelihood of its occurrence.6 It is a class effect, and generally recurs if any other ACE inhibitor is reintroduced.

A2R blockers

Angiotensin 2 receptor (A2R) blockers are commonly used as a first substitute when ACE inhibitor cough appears, though they have a similar side effect profile to ACE inhibitors. However, cough can still occur with A2R blockers but is typically three to four times less common.7,8 Cough recurrence rates are also lower with A2R blockers but they should not be overlooked as a cause of chronic cough.

β-blockers

Cough may be the initial manifestation of drug-related airway hyper-responsiveness or bronchoconstriction that is described with β-blockers; associated wheeze and dyspnoea may occur. β-blockers (including eye drops) cause bronchoconstriction via bronchial β2 receptor blockade. A meta-analysis has confirmed no evidence of long-term decline in lung function in reversible obstructive lung disease with cardio-selective β-blockers (atenolol, metoprolol, bisoprolol). A short-term decline of 8% in forced expiratory volume in second (FEV1) was seen, but this was not sustained.9 In addition, long term respiratory symptoms and use of inhaled β-agonists were not increased. Carvedilol has also been shown to be well tolerated (in terms of lung function indices and aerobic performance) despite being a non-selective β-blocker, possibly because of mild bronchodilation from its α-blocking activity.10

NSAIDs

Aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, diclofenac, naproxen, and indomethacin, can cause bronchoconstriction in 5% of people with asthma by driving cysteinyl leukotriene production and inhibiting cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1). Symptoms may occur within 30 minutes to 3 hours of ingestion and be associated with facial flushing and nasal and upper airway symptoms. Leukotriene antagonists (as part of asthma therapy) are particularly helpful in treating these symptoms.

Calcium antagonists

Calcium antagonists relax the lower oesophageal sphincter pressure and in dose-dependent fashion impair oesophageal clearance and cause reflux cough (amongst other symptoms). Reflux cough should be particularly suspected with cough on phonation, throat clearing, after meals, or cough on rising/stooping; it may also be the only manifestation of reflux (without dyspeptic symptoms).11 In studies of reflux-related symptoms, verapamil and amlodipine were reported as causing more reflux symptoms than diltiazem.12 Reflux cough may also be aggravated by other drugs including nitrates via similar effects on lower oesophageal sphincter pressure. Stopping the drug and avoiding other aggravating drugs may be the only intervention necessary. Resolution of symptoms may take up to 3 months.

Summary

-

1

Consider the drug history carefully before investigating for other causes of cough; stopping the relevant drug is the key to treatment

-

2

ACE inhibitor cough may not arise for 6 months and can take 3 months to subside on stopping the drug, and A2R blockers can also cause cough (although less commonly)

-

3

β-blockers can be cautiously trialled in mild-moderate reversible obstructive lung disease. Cardio-selective β-blockers are preferable (atenolol, metoprolol) or combined α- and β-blockers (carvedilol)

-

4

Consider occult asthma or bronchial hyper-reactivity with newonset cough following aspirin or NSAIDs.

-

5

When reflux cough is suspected, don't forget calcium antagonists as a cause and nitrates.

-

6

Drug-related cough may be the beginning of a more extensive syndrome and many drugs can cause such syndromes; consult Pneumotox database for quick assistance

References

Medford AR . Drugs and Toxins. In: Maskell N, Millar AB, ed. Oxford Desk Reference Respiratory Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. Chapter 16.1, p. 384–9.

Foucher P, Camus P, GEPPI (Groupe d'Etudes de la Pathologie Pulmonaire latrogene). The drug-induced lung diseases. Pneumotox online. http://www.pneumotox.com/

Irwin RS . Baumann MH, Bolser DC, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129(1 Suppl):1S–23S. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S

Dicpinigaitis PV . Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129(1 Suppl):169S–1735S. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.169S

Tseng DS, Kwong J, Rezvani F, Coates AO . Angiotensin-converting enzyme-related cough among Chinese-Americans. Am J Med 2010;123:183.e11–e15.

Boulet LP, Milot J, Lampron N, Lacourcière Y . Pulmonary function and airway responsiveness during long-term therapy with captopril. JAMA 1989;261:413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1989.03420030087036

Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, for the ONTARGET investigators et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1547–59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0801317

Matchar DB, McCrory DC, Orlando LA, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers for treating essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:16–29.

Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE . Cardioselective beta-blockers in patients with reactive airway disease: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:715–25.

Sirak TE, Jelic S, Le Jemtel TH . Therapeutic update: non-selective beta- and alpha-adrenergic blockade in patients with coexistent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:497–502. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.063

Morice AH, McGarvey L, Pavord I et al. BTS guidelines. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax 2006;61:i1–i24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2006.065144

Hughes J, Lockhart J, Joyce A . Do calcium antagonists contribute to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and concomitant noncardiac chest pain? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;64:83–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02851.x

Acknowledgements

Handling editor Hilary Pinnock

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Medford, A. A 54 year-old man with a chronic cough — Chronic cough: don't forget drug-induced causes. Prim Care Respir J 21, 347–348 (2012). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00078

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00078