Diagnosis and early management of inflammatory arthritis

BMJ 2017; 358 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3248 (Published 27 July 2017) Cite this as: BMJ 2017;358:j3248

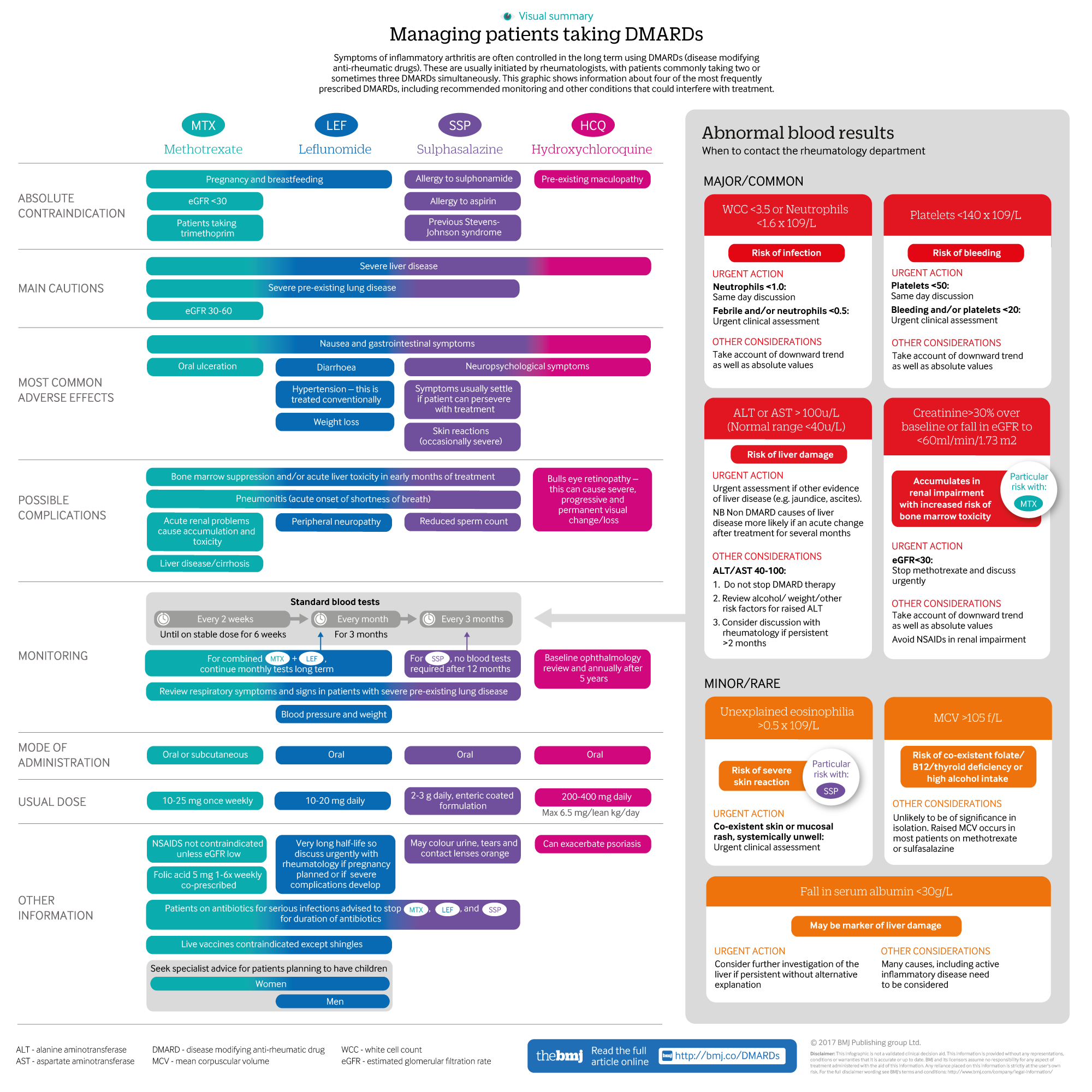

Infographic available

A visual summary of the four most frequently used DMARDs, including recommended monitoring and conditions that may interfere with treatment

- Joanna Ledingham, consultant rheumatologist1,

- Neil Snowden, consultant rheumatologist2,

- Zoe Ide, patient3

- 1Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth, UK

- 2Pennine MSK Partnership, Integrated Care Centre, Oldham, UK

- 3National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society, Maidenhead, UK

- Correspondence to J Ledingham: jo.ledingham{at}porthosp.nhs.uk

What you need to know

Consider inflammatory arthritis in anyone with acute or subacute onset of joint pain, early morning stiffness, and soft tissue swelling

Early diagnosis and treatment with disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDS) and corticosteroids improves function and symptomatic and radiographic outcomes

Patients need rapid access to specialist advice during flares

Prescription and monitoring of DMARDs can be shared between specialists and non-specialists if pathways and communication are clear

Specialists are best placed to guide changes in DMARDS or steroid treatment

Autoimmune inflammation affects the joints of people with inflammatory arthritis. No definitive cause has been identified, despite extensive research. An environmental trigger in a genetically predisposed individual seems to be the most likely mechanism.1

About 80-100 adults in 100 000 develop inflammatory arthritis every year.2 3 Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common inflammatory arthritis, affecting approximately 500 000 people in the UK.4 Spondylo-arthropathies, which include psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis, are slightly less common. In ankylosing spondylitis inflammation occurs mainly in the spine, but peripheral arthritis can occur.5 Inflammatory arthritis primarily affects people of working age, and within 10 years of diagnosis around 40% of people with rheumatoid arthritis are unable to work.6

Systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials show that early treatment can control symptoms, induce remission, minimise irreparable damage, and protect against the mortality and morbidity associated with inflammatory arthritis, especially cardiovascular. Guidelines7 and quality standards8 from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommend early aggressive treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. This approach has been shown to be cost effective,9 and management principles for rheumatoid arthritis are broadly applicable to all forms of inflammatory arthritis. This clinical update, aimed at non specialists, provides information on the diagnosis and early management of inflammatory arthritis.

Sources and selection criteria

We performed a Pubmed search on the terms “early inflammatory arthritis” and “early rheumatoid arthritis,” which produced 169 references. This was reviewed and supplemented with references from personal archives and the literature review performed as part of the recent revision of the British Society for Rheumatology DMARD guidelines.36

How do patients with inflammatory arthritis present?

Consider inflammatory arthritis in patients who develop joint symptoms, especially if they have a family history of inflammatory arthritis, psoriasis, or inflammatory bowel disease, or a personal history of conditions detailed below.

Most patients with inflammatory arthritis present with joint swelling, pain, tenderness, stiffness, and warmth in the joints. Symptoms can be acute, developing over days or weeks, can fluctuate, but can also develop more slowly, with no initial obvious joint swelling (arthralgia). Systemic features including fatigue are common. Other pointers for inflammatory arthritis include sudden onset of disabling, severe joint pain and/or joint pain that rapidly and progressively increases. Septic arthritis will usually present as a mono-arthritis and can be difficult to distinguish from other inflammatory arthropathies. Refer patients for specialist review urgently (within 12 hours) and avoid prescribing antibiotics before referral to optimise the chances of identifying organisms and antibiotic sensitivity.10

Rheumatoid arthritis—usually presents with symmetrical inflammation of the small joints, typically the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and metatarsophalangeal joints. Rheumatoid arthritis can be associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as thyroid disease, inflammatory lung disease, bronchiectasis, and eye disorders such as sicca syndrome, scleritis, and episcleritis.11 In older patients, rheumatoid arthritis more often presents with polymyalgia and with large joint involvement.12

Spondylo-arthropathies—patients typically have an asymmetrical pattern of large joint disease, with fewer joints affected than in rheumatoid arthritis. In psoriatic arthritis, the distal interphalangeal joints can be affected.13 14 Spinal inflammation might occur in any of the spondylo-arthropathies and typically causes pain and stiffness that is worse at night and in the morning, and which eases with activity and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).5 15 Patients can also present with eye disorders such as iritis.16 Linked psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease often predate the onset of inflammatory arthritis but can develop many years after the onset of an arthropathy.15 Symptoms of reactive arthritis can develop after gastrointestinal or asymptomatic genito-urinary infections.17

How is inflammatory arthritis diagnosed?

Diagnosis is clinical, based on the presence of joint pain, early morning stiffness (>1 hour), and soft, often warm swelling around joints. An example of synovitis of the knee is shown in figure 1⇓.

Other differential diagnoses for inflammatory arthritis include crystal arthropathies (gout and pseudogout), which tend to present with more acute onset inflammation (within hours) in a single joint, and osteoarthritis, which presents without the inflammatory features described above.

Acute inflammatory mono-arthritis is most often caused by crystal arthritis,10 but sepsis should be considered/excluded. Self limiting viral arthritis can be hard to differentiate clinically from early rheumatoid arthritis. Commonly there is no definite diagnosis during the early weeks of disease.18

Blood tests

If you suspect inflammatory arthritis clinically, check inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentary rate, C reactive protein, plasma viscosity) and rheumatoid factor. Normal or negative results do not exclude inflammatory arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid factor is negative in up to a third of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and in most patients with spondylo-arthropathies.19 20

Full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, and bone biochemistry as a baseline help guide treatment and identify any relevant comorbidities.

Imaging techniques

Imaging is not routinely recommended before referral. Rheumatologists generally have access to same day plain radiography if required to guide management. Radiographs of the hands and feet can help identify erosions or typical features of inflammatory arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, and sacro-iliitis can be identified in spondylo-arthropathies. Radiography of other joints is not usually indicated in early disease, as it does not alter management plans. An example of the effects of uncontrolled inflammatory arthritis is shown in figure 2⇓.

Fig 2 Radiographs showing severe, irreversible changes secondary to aggressive inflammatory arthritis

Ultrasound can help clarify a diagnosis of peripheral joint inflammatory arthritis and is available in many early arthritis clinics.18

When to refer?

Refer patients to a specialist immediately if there are clinical features of a potential inflammatory arthritis; NICE recommends referral within three working days.8 Avoid prescribing steroids before referral, so that a diagnosis can be confirmed and appropriate treatment started as quickly as possible. In our clinical experience, prescription of steroids can mask key clinical features and delay diagnosis. When communicating with rheumatologists, report key symptoms and signs such as joint pain, early morning stiffness, and swelling around joints, to help alert them to the possibility of inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology departments usually offer urgent appointments if they are aware that you suspect inflammatory arthritis. In the UK patients can be seen within 12-48 hours, as shown by national audit results.18 21

What is the evidence for early referral and treatment of inflammatory arthritis?

Systematic reviews of 92 studies support early treatment of inflammatory arthritis with disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), within three months of symptom onset, to improve function and reduce disability and long term joint damage.22 23 This is referred to as the three month “window of opportunity.” Treatment can be started by rheumatologists for patients with undifferentiated arthritis with poor prognostic markers, such as active disease and positive auto-antibodies.24

Systematic reviews of 15 studies also support a management strategy of frequent review and escalation of treatment to minimise inflammation (“treating to target”), and early use of multiple DMARDs produces the best outcomes.25 26 Using this strategy, randomised controlled trials show that remission (effectively absence of joint inflammation) can be achieved in about 65% compared with 10%-20% of those treated less intensively.27

UK registry data suggest that the need for joint replacement surgery in people with rheumatoid arthritis is declining by about 5% per year, despite an ageing population.28 Intensive reduction of inflammation might almost normalise cardiovascular risk, which is doubled in association with rheumatoid arthritis.29 30

What treatments are used to manage early disease?

Management principles for all forms of inflammatory arthritis share similarities; namely immediate treatment of inflammatory symptoms followed by longer term modulation of inflammation using DMARDs until remission is achieved. NICE recommends that DMARDs are started within six weeks of referral to secondary care.8

Bridging treatment until remission—offer patients treatment with analgesics or NSAIDs in the first instance to control inflammatory symptoms such as pain and stiffness. Specialists might recommend corticosteroids, often intramuscular rather than intravenous or oral, early in the disease for their rapid effect.31

DMARDs—are initiated by rheumatologists. The ways in which DMARDs modulate inflammation are complex and not fully understood. Key information including dose, route of administration, contraindications, and monitoring schedules for the most commonly prescribed DMARDs is provided in the supplementary infographic⇓.

NICE quality standards for rheumatoid arthritis with achievement rates for years 1 and 2 of the national audit

NICE recommends early use of combinations of DMARDs for the management of rheumatoid arthritis.7 8 This might include two or more DMARDs started together, or initiation of one DMARD followed shortly by a second.

Systematic reviews suggest that intensity of treatment and reduction of inflammation are more important than any particular drug regime in reducing pain and disability, so choice of treatment can be dictated by patient specific factors and cost effectiveness.27

The most commonly used DMARDs are methotrexate, sulphasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, and leflunomide, as they have been shown in randomised controlled trials and observational studies to have the best efficacy and tolerability.32 The choice of DMARD depends on contraindications, comorbidities, risks, and patient choice, such as their wish to conceive.33 Methotrexate tends to be the most commonly used drug for reasons of efficacy, safety, and tolerability.32 34

DMARDs can take 8-12 weeks to be effective.35

What adverse effects might patients experience?

Most adverse reactions occur within the first three months of treatment.36 Minor adverse effects, such as nausea, mouth ulcers, and abdominal symptoms settle with time, dose adjustments, or with additional treatments. Many patients tolerate DMARDs reasonably well.37

Intercurrent illness and drug interactions that reduce renal function can increase toxicity, particularly of methotrexate.

Most DMARDs can cause pneumonitis, and there is no clear evidence for an increased risk with any specific drug 36 38 39 Pneumonitis is extremely rare (0.1%-1% of treated patients) and other causes for lung symptoms are much more common. Consider pneumonitis in any patient developing acute breathlessness without an obvious cause. Most pneumonitis develops during the first year of treatment.39

How are patients on DMARDs monitored?

All patients on DMARDs, with the exception of those on hydroxychloroquine, need to be monitored for complications of the bone marrow, kidney, and liver. Recently updated guidance simplifies blood monitoring protocols,36 however monitoring schedules vary for individual patients depending on co-morbidities. Key requirements are detailed in the supplementary infographic⇑.

In the early stages of inflammatory arthritis, NICE recommends that patients are reviewed by a specialist approximately monthly, so that treatment can be adjusted to control active disease and to manage any disease or treatment complications.

Minor changes in blood test results are common and usually do not require an adjustment in DMARD dose. British Society for Rheumatology guidelines recommend discussing any notable new abnormalities (supplementary infographic⇑) with the rheumatology unit either urgently or within one working day. As well as responding to absolute values, trends in results (such as gradual decreases in white blood cell count, or an increase in liver enzymes) are important. Inform the rheumatology unit if DMARDs are discontinued.

How to adapt routine care for those taking DMARDS

Infection—unless there is evidence of bone marrow suppression, it is thought that other factors (such as chronic comorbid disease, steroids, diabetes, and active inflammatory arthritis) are generally more important contributors to infection risk than DMARDs.36 40 41 Latest guidelines advise that patients stop most DMARDs if they have severe infections involving admission to hospital and/or requiring parenteral antibiotics.36 In view of the serious interaction of trimethoprim with methotrexate, these drugs should not be co-prescribed. Clinical signs such as fever might be blunted in patients with infection such as pneumonia.

Prevention—offer influenza and pneumococcal immunisation to all patients taking DMARDs due to the increased risk and severity of these infections through immunosuppression. Hepatitis B vaccination should be offered to high risk groups, ideally before starting DMARDs. Discuss vaccination for shingles (which is usually recommended) with specialists.42 43 Avoid other live vaccines.

Surgery—DMARDs do not need to be stopped routinely when patients undergo surgery.36

What other aspects of patient care need attention?

Patients often suffer profound fatigue, sleep disturbance, and problems with joint function in addition to joint symptoms.44 45 Psychological problems have also been identified in approximately 20% of patients.46 47 Allied health professionals, members of the multidisciplinary team, and patient organisations have key roles in managing all these components of the disease.48 49

How should flares be managed?

Flares can occur at any time and most patients will experience at least one flare within a three year period.50 Flares are less common with intensive treatment.51 They can be triggered by factors such as stress, intercurrent infections, and non-compliance with treatment, but in other cases there is no clear trigger. Recommend referral back to rheumatology to escalate treatment. Flares are usually managed in the short term with corticosteroids (usually intramuscular or intra-articular) but also with escalation of DMARD treatment. Frequent flares lead to more joint damage and disability.51

What is the prognosis for patients with inflammatory arthritis?

Meta-analyses of historical case series in rheumatoid arthritis consistently show an increased mortality in this disease, with a loss of life expectancy of 5-7 years.52 Modern treatments are very effective in controlling joint inflammation and this can translate into improved survival; emerging epidemiological evidence suggests that recently diagnosed cohorts might have no excess mortality.53

Other support for patients

Rheumatology teams can provide information on inflammatory arthritis and its treatment, promote self management through education, and provide access to urgent advice. Many departments provide personalised care plans for patients, including targets for disease control. These are usually disease activity scores assessing pain, inflammatory markers, and number of tender and swollen joints, but can also include targets for function and radiographic change.

Information is available on how to protect joints and pace activities. Patients are encouraged to undertake regular exercise, although inflamed joints need to be protected from excessive strain.56 57

Ask about a patient’s ability to work (where relevant) and their mental health, in line with national initiatives. Offer support, such as signposting to the various charities that support patients with arthritis (eg, the National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society and the National Ankylosing Spondylitis Society). Supply fit notes and make referrals to occupational health teams when required.54 55

Since 2014, NHS Rheumatology services in England and Wales have been required to participate in the National Clinical Audit for Rheumatoid and Early Inflammatory Arthritis. The first two years of this audit gathered data from all incident cases of adult inflammatory arthritis, from referral through the first three months of specialist care. National performance data for the NICE quality standards achievement rates in inflammatory arthritis are shown in table 1⇑. Regional and local level data on these and on patient reported outcomes, experience, and work have been reported.18 21 The key messages from this audit are that patients wait too long for referral and specialist assessment, leading to delays in treatment. A second phase of this audit is due to start in 2018.

Education into practice

How would you assess whether patients in your practice with symptoms suggestive of inflammatory arthritis are being referred to a rheumatologist within the three working days recommended by NICE? What might the barriers be?

Before reading this article, did you know about the other symptoms that patients with inflammatory arthritis experience, such as profound fatigue and sleep disturbance? How might you address these with your patients?

How familiar are you with requirements for DMARD monitoring? What systems do you have in place to monitor results before issuing DMARD prescriptions? Are there any changes you might make?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

Zoe Ide, a patient with rheumatoid arthritis, actively contributed to this article and has provided details of her experience as a patient in the patient commentary (box 1). She has given input to the design, writing, construction, and review of this article, with a particular focus on the aspects of patient care that need attention alongside a timely diagnosis. These include fatigue management, supporting ability to work, psychological wellbeing, and signposting to patient organisations, which have been incorporated into the article.

Box 1: Patient experience of early inflammatory arthritis

I started to experience a general feeling of “achiness” at the end of a busy summer weekend. On Monday I was unable to lift my left arm without pain, and was stiff and tender around my shoulders. The sudden lack of function worried me so I visited my doctor. He moved the arm through its range, explained that I had sprained the shoulder, and told me to “stop swinging from the chandeliers.” Painkillers and rest were the cure.

Over the next few months there would be weeks when I felt completely normal, with a day or so when similar symptoms in shoulders, hips, and knees would return. The pain on these “off” days was worse in the morning. I remember during these episodes standing all the way into work on the bus and train, an hour’s journey, to avoid movement. Being in my thirties at the time, with a busy life and stressful job, I ignored what was happening, pushing through with painkillers and sometimes alcohol.

When my feet started to hurt and getting out of bed was tortuous, I updated my doctor. He examined my feet by sight and took blood, which showed a high rheumatoid factor and raised inflammation but “nothing significant.” It was explained that he could refer me to a rheumatology specialist, but once there I would be managed in the same way as he would do at the surgery, on painkillers with a watching brief. I agreed to see if I got better or worse.

I reluctantly returned to my doctor some time later when it became difficult to manage stairs and a knuckle had swelled. Luckily, that day I saw a locum who examined me, reviewed my history, and referred me immediately to secondary care. I was seen by my first rheumatologist 18 months or so after visiting my doctor for the first time.

DMARD monitoring patient perspective

As a patient I have found it helpful to keep a close eye on my DMARD monitoring. Having been registered with four surgeries in 10 years, I have seen that there are variations in how monitoring is done, and although generally good, there have been some challenges. I recently discovered that the full blood count record was missing from a methotrexate monitoring result for which I had already been told my results were normal. As I was feeling unusually tired and was about to increase my dose, I believed a further test was needed but was informed by surgery administrative staff that this was not necessary for methotrexate, though they would let my doctor know. I received no follow-up from my doctor, which was very unsettling at the time, though I have raised this again and there have been no problems since.

Additional educational resources

Helpful resources for patients and the public, with information on diseases, treatments and support

Arthritis Research UKwww.arthritisresearchuk.org/

Arthritis Care www.arthritiscare.org.uk

National Ankylosing Spondylitis Society https://nass.co.uk/

National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society www.nras.org.uk

Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Alliance www.papaa.org

Arthurs Place: support for young adults with arthritis http://arthursplace.co.uk/

Footnotes

We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Provenance and peer review: encouraged; externally peer reviewed.